Maintenance, Tips, How-Tos

Photo Tutorials Will Be Added On An Ongoing Basis

Scroll Down The Page To Find What You're After, In The Order Shown:

1 • Carb Fuel Joint O-ring & Fuel Line Replacement (1986-97)

2 • Rear Caliper Sleeve Replacement ('86-87)

3 • Master Cylinder Rebuild

4 • Sight Glass Replacement

5 • Carburetor Bowl Gasket Replacement

6 • Fuel Tank Sealing

7 • Screw-type Drive Chain Master Link Install

8 • Muffler Installation Tip

9 • Fork Leg Refinishing

10 • Muffler Refurbishing - OEM

11 • Muffler Refurbishing - Yoshimura

12 • Decal Removal (No Mar)

13 • Small Coolant Hose Generic Replacement

14 • Reshaping A Chain Guard

15 • Steering Head Bearing Replacement

16 • Refurbishing Paintwork

17 • Carburetor Removal

18 • Carburetor Disassembly & Cleaning

19 • Preparing For Carb Sync

20 • Carburetor Installation

21 • Carburetor Synchronising

22 • Chain Slider Fix ('86-87)

23 • Brake Caliper Disassembly

24 • Mirror Refurbishing

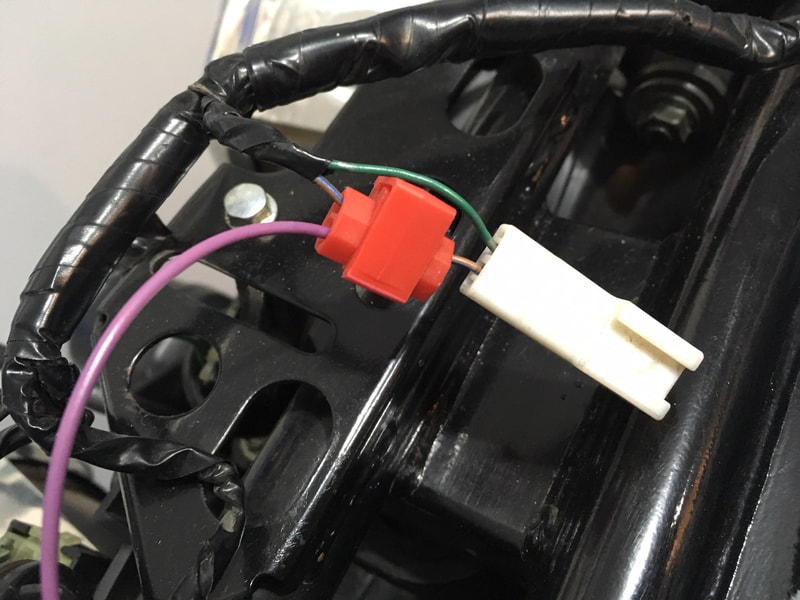

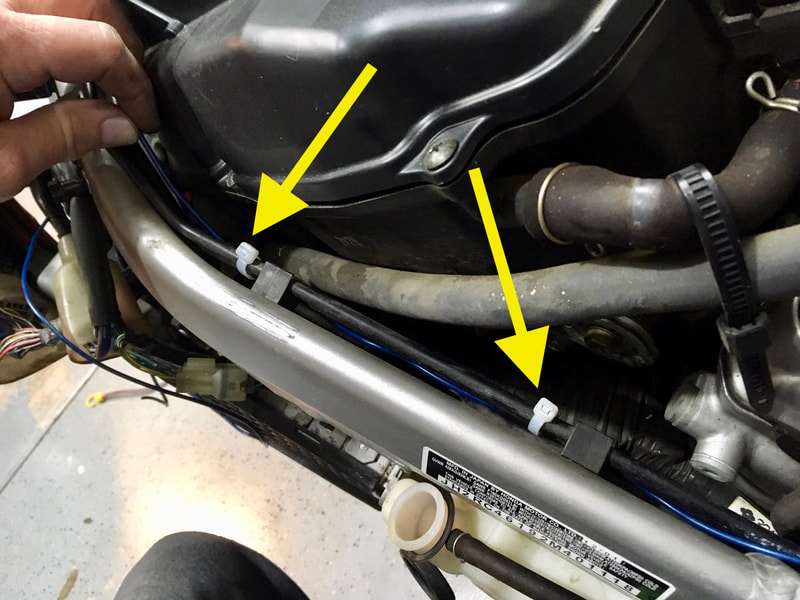

25 • Gas Siphoning Made Easy

26 • Plugging the PAIR Ports

27 • Eliminating The Stator Wiring Connector

28 • Charging System Check & Diagnostics

29 • Windscreen Refurbishing & Plastics Care

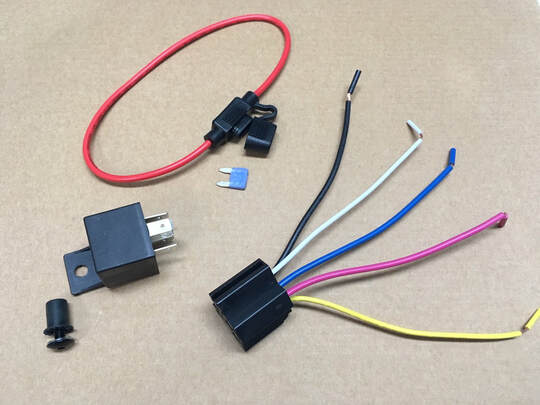

30 • Electrical Relay Installation

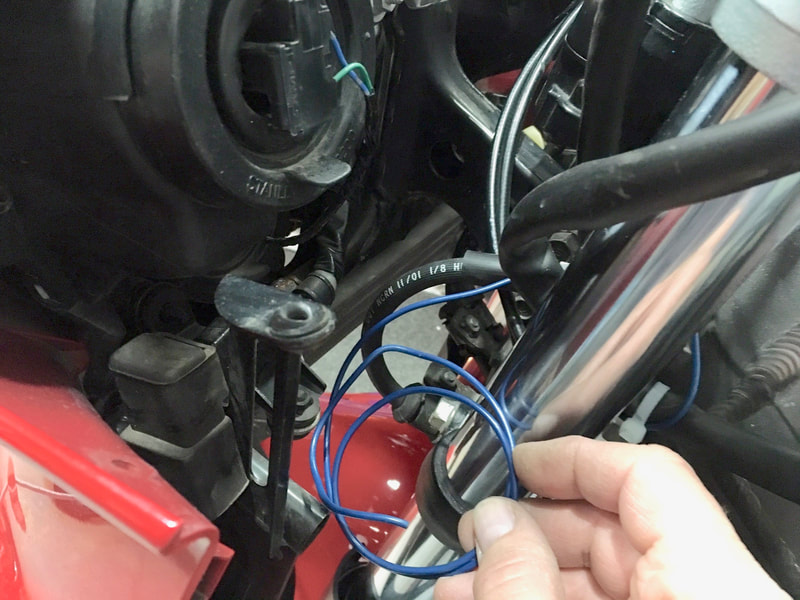

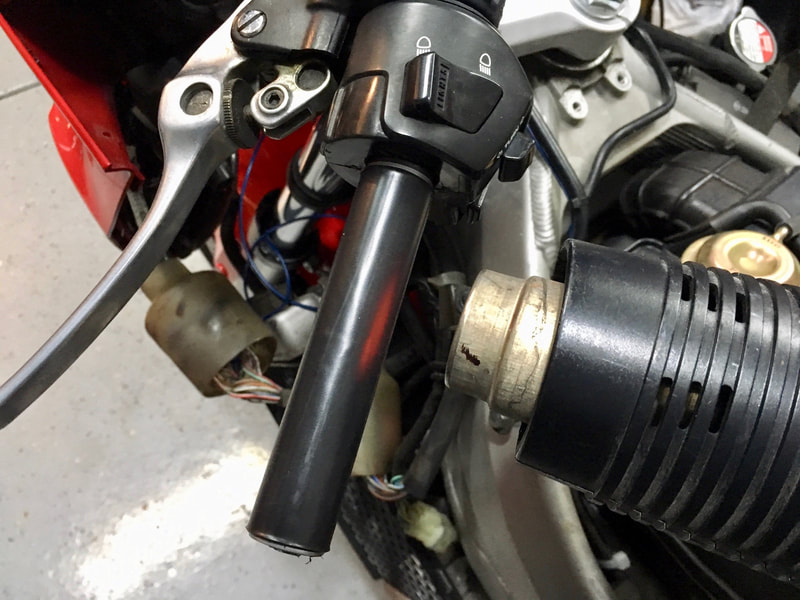

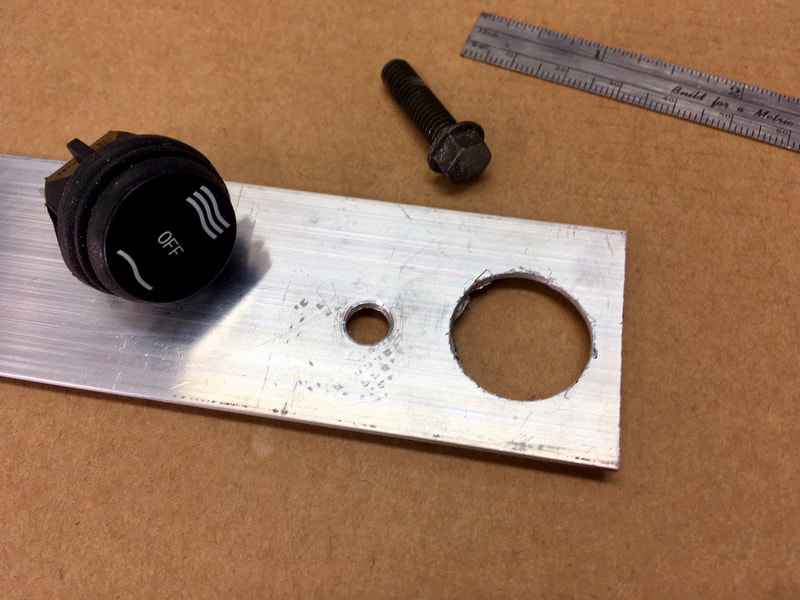

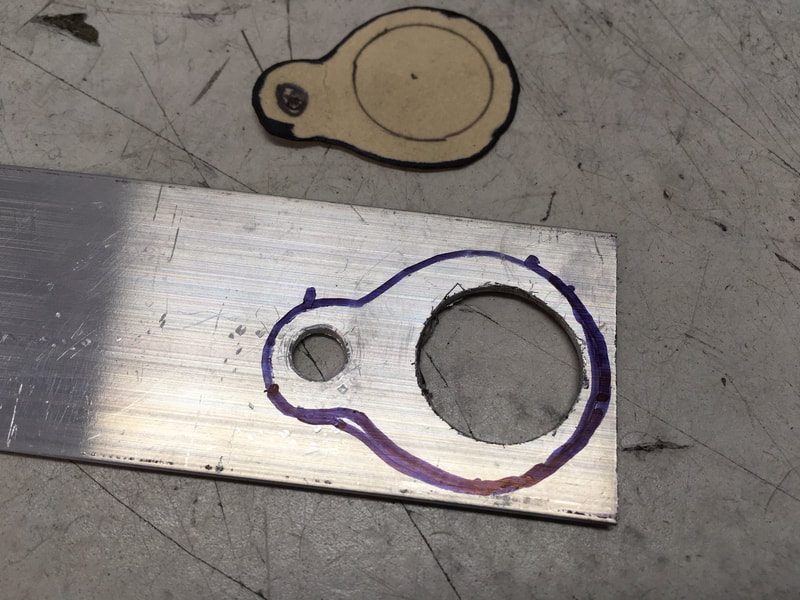

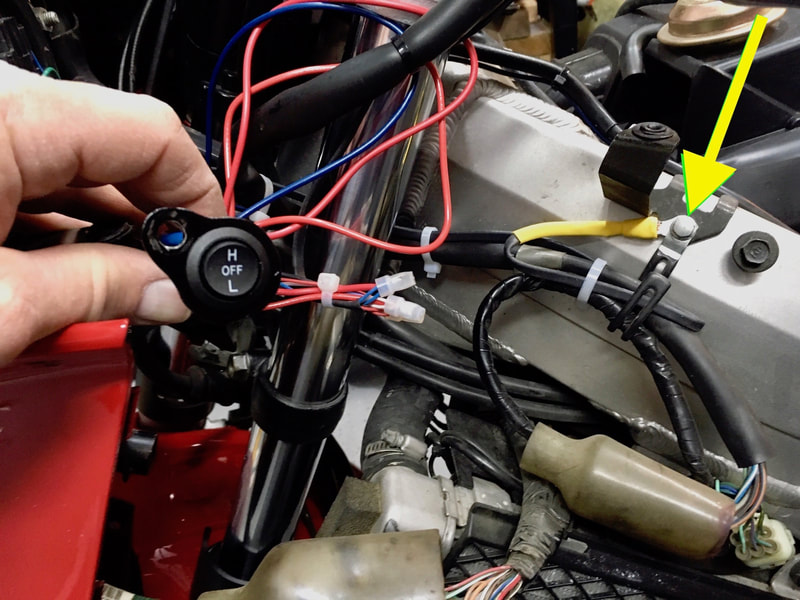

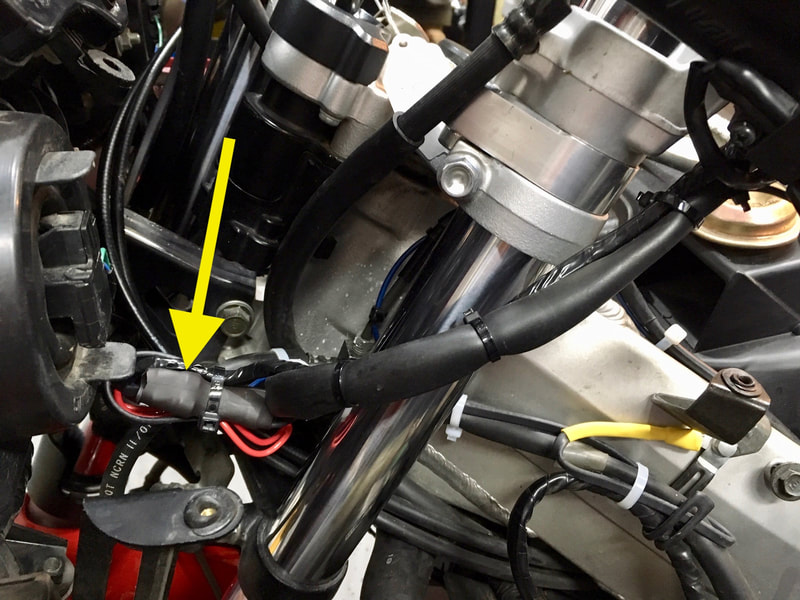

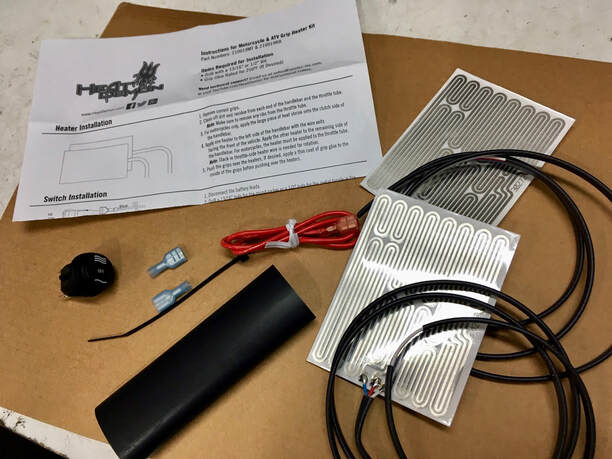

31 • Heated Grips Installation

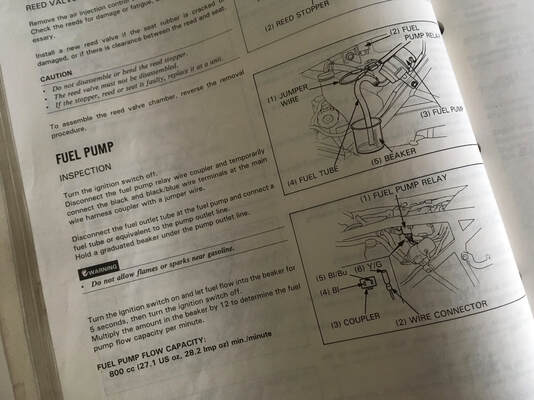

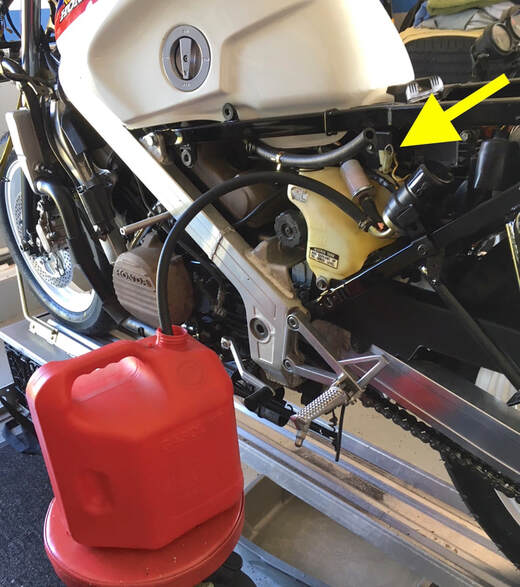

32 • Priming Carbs, Testing A Fuel Pump, Empty A Fuel Tank

33 • Trimming or Eliminating Passenger Peg Brackets

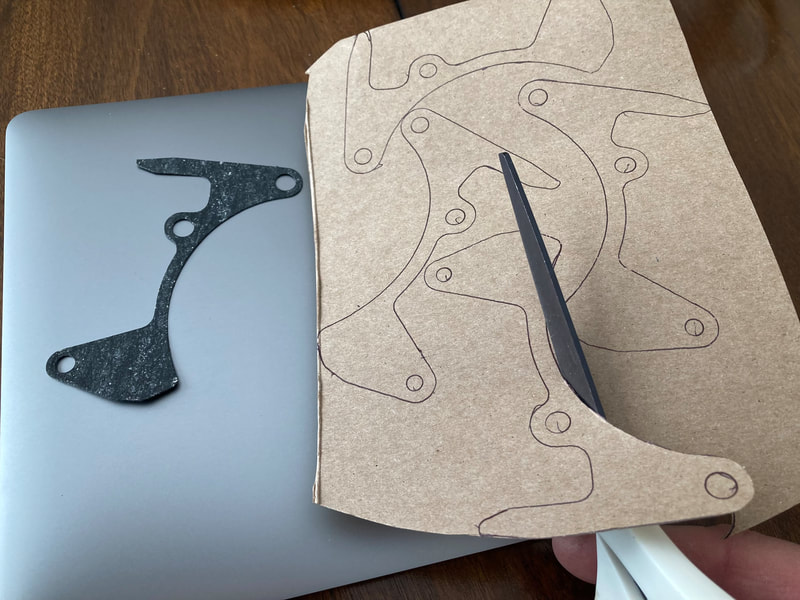

34 • DIY Gaskets

35 • Modify Fenders, Front & Rear — 2d-Gen

36 • Clutch Slave Cylinder Overhaul

37 • Refurbishing Exhaust Pipes

38 • Installing Windscreen Molding — 2d-Gen

39 • Chain & Sprocket Installation

"The Shop Blog" PDF Index 2015-24

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

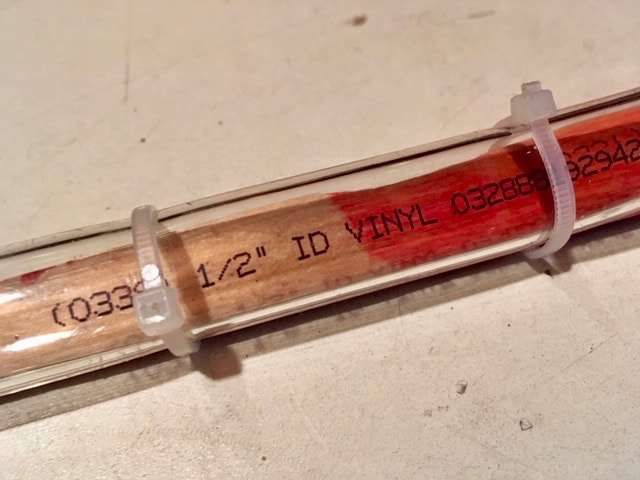

1. Carb Fuel Joint O-ring & Fuel Line Replacement (1986-97)

Honda calls their plastic fuel distribution tubes "fuel joint sets," but I just call them tubes. Their job is to distribute fuel from the inlet line to each carb. There's two tubes, one for carbs 1 & 3, and one for carbs 2 & 4. The point where they enter the carburetor needs to be removable for service and also have a bit of flexibility in use, so they're sealed with o-rings. Like all of our rubber fuel parts they were not designed with modern fuel chemicals in mind, like ethanol. This fact, combined with heat and age, makes them a weak point in the fuel system. I replace them as a matter of course on all my projects, along with the two flexible inlet lines. Today we have the advantage of VITON o-rings and TYGON fuel line which can stand up to anything the chemical engineers can throw our way.

The plastic tubes with o-rings are still available from Honda for about $42 each. There's also an eBay seller who offers metal replacement tubes/o-rings for about $85 a set. On my "Products" page I offer a repair kit consisting of four o-rings, two fuel lines and clamps for $20. Whichever direction you choose, the installation is the same, and here's how I do it....

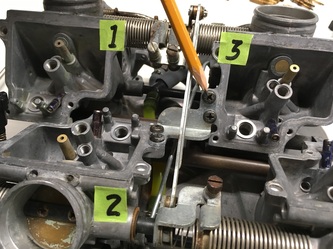

Note: the carbs are numbered as follows: Viewed from the rider's seat;

#1 is left rear

#2 is left front

#3 is right rear

#4 is right front.

Note: the carbs are numbered as follows: Viewed from the rider's seat;

#1 is left rear

#2 is left front

#3 is right rear

#4 is right front.

To paraphrase Hippocrates, "First, do no harm." The idea here is to separate the carbs from the plenum and one another in order to slide the tubes away, replace the o-rings, and reassemble, disturbing the carb set as little as possible. And remember that the tubes are plastic so be gentle.

Here's the basic required tools: impact driver, screwdrivers, needle nose pliers, cleaning brush, cleaning solvent (but not brake cleaner) and oil. A dental pick or tiny screwdriver is also useful for removing the old o-rings.

Here's the basic required tools: impact driver, screwdrivers, needle nose pliers, cleaning brush, cleaning solvent (but not brake cleaner) and oil. A dental pick or tiny screwdriver is also useful for removing the old o-rings.

Like everything mechanical, this process is easier with the carb rack cleaned and disassembled; see tutorial 18, "Carburetor Cleaning, Disassembly, Reassembly." I will refer to the 1986-87 model with separate references to the later models where necessary. Click on photos to enlarge.

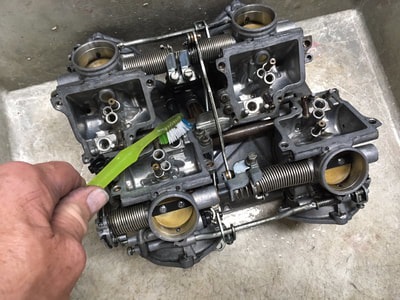

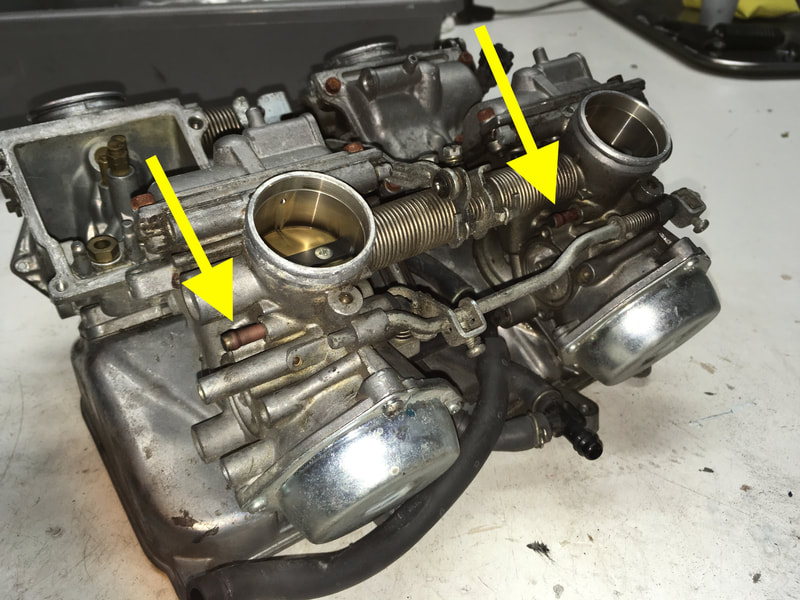

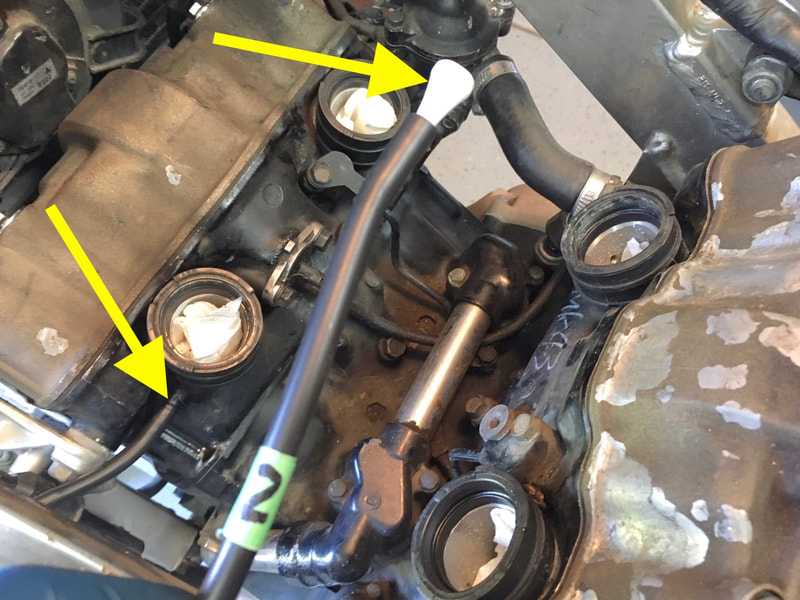

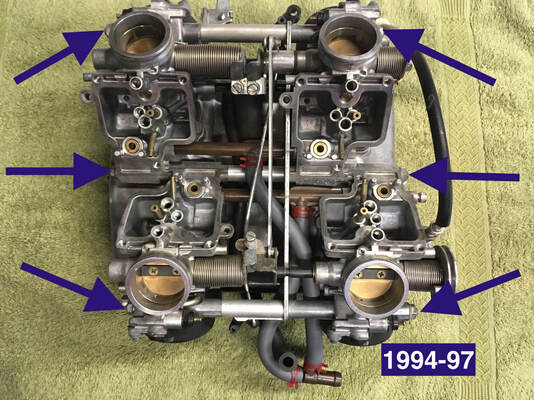

We begin by removing the plenum screws — 8 inside the plenum (16 for '94-97) plus two on the sides. Note: '90-93 do not have the two side screws, while the '94-97 have six 10mm side nuts holding long metal alignment dowels (the longer one is the center of the three). The plenum and side screws may require an impact driver to loosen (carefully). With the carb rack then turned upside down (plenum down) on the bench with carbs #2 & 4 facing me, remove the center bracket. Note: '94-97 have no center bracket. The throttle/choke linkages connecting #2 and #3 will remain in place.

('86-87 carbs shown)

We begin by removing the plenum screws — 8 inside the plenum (16 for '94-97) plus two on the sides. Note: '90-93 do not have the two side screws, while the '94-97 have six 10mm side nuts holding long metal alignment dowels (the longer one is the center of the three). The plenum and side screws may require an impact driver to loosen (carefully). With the carb rack then turned upside down (plenum down) on the bench with carbs #2 & 4 facing me, remove the center bracket. Note: '94-97 have no center bracket. The throttle/choke linkages connecting #2 and #3 will remain in place.

('86-87 carbs shown)

(Right) Location of the six nuts securing the carb rack; '94-97

With all the screws/bolts off, the plenum can be lifted off.

On the '90-97 (below left, 1995 pictured) first note how the four velocity tubes are located to help with reassembly. It may help to mark the tubes with a reference line to the top screw of the diaphragm cover (below right, 1993 pictured).

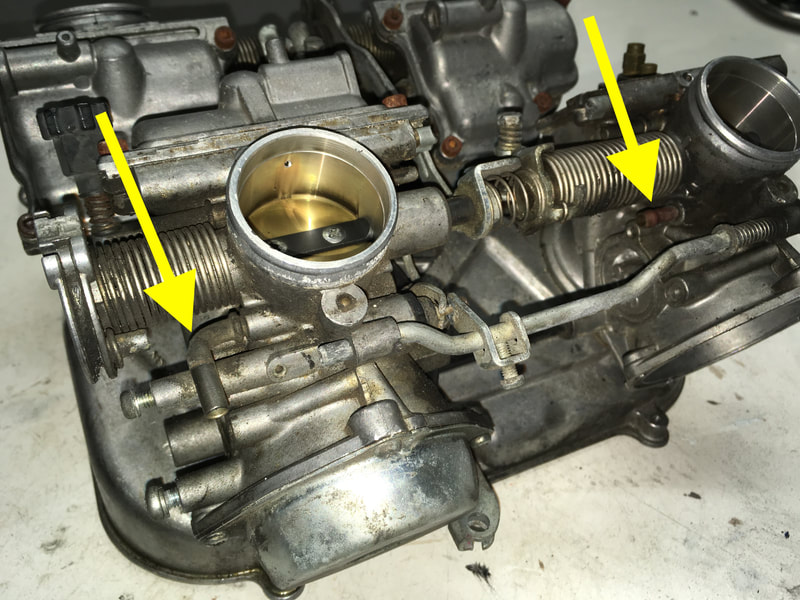

I now remove the tiny sync springs — not the screw and spring, just the springs underneath. TIP: It helps to first unscrew them 4 or 5 turns and, when reinstalling the spring during reassembly, screw the same amount back in — this is important, as it helps retain what "sync" the carbs began with. The #3 sync spring needn't be removed ('86-93); same with the #2 for '94-97.

Note: 1986-93 has no adjustment screw on #2 carb, while '94-97 has no adjustment screw on #1 carb. These are the "base" carbs for syncing purposes.

Note: 1986-93 has no adjustment screw on #2 carb, while '94-97 has no adjustment screw on #1 carb. These are the "base" carbs for syncing purposes.

Also remove the two large throttle shaft springs — the light ones between the sync screws, not the long heavy springs.

Finally, remove the choke shaft bracket at #4 by loosening its set screw and sliding the bracket off the shaft ('86-87 shown). Also loosen the same bracket at #2, visible in the upper left corner of this photo. This will allow the choke shaft to slide free as we separate the carbs.

On '90-93 loosen the brackets and slide the rod free to the right. The spring and bracket will fall free.

For '94-97, see below.

On '90-93 loosen the brackets and slide the rod free to the right. The spring and bracket will fall free.

For '94-97, see below.

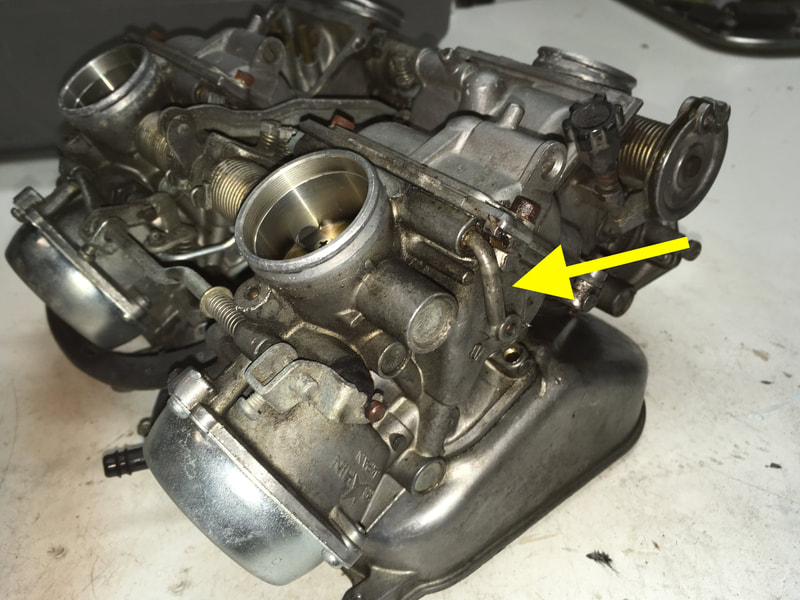

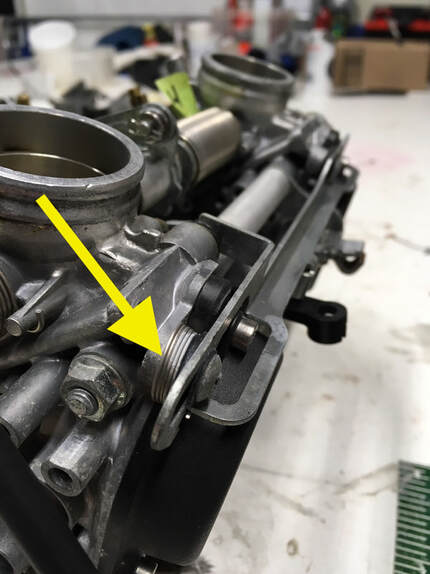

(Right) The two sliding choke rods on the '94-97 carbs are secured by two screws on each rod. Note carefully the arrangement of these screws, their washers and the spring (arrow). The choke will not operate smoothly if these are not positioned correctly upon reassembly. Also note how the choke mechanism is slotted into the long bar in order to slide it side-to-side — important for correct reassembly.

I wriggle completely free all four carbs ('86-87 pictured). Note that the carb bases are located to the plenum on dowel pins with large sealing o-rings.

Now is the time to note how the lines are routed, you may want to take photos. I then cut the old hardened fuel lines (assuming they’re being replaced) as short as possible to get them out of the way (don't pull on them, you could break the plastic tubes) and gently free the #2/4 fuel tube and then the #1/3 tube from the carb bodies.

Now is the time to note how the lines are routed, you may want to take photos. I then cut the old hardened fuel lines (assuming they’re being replaced) as short as possible to get them out of the way (don't pull on them, you could break the plastic tubes) and gently free the #2/4 fuel tube and then the #1/3 tube from the carb bodies.

(Right) On the '94-97 note the small bracket at the bottom of photo. Note exactly how this bracket was located, you won't want to forget it during reassembly.

The tubes are identical — just installed in a mirrored fashion ('86-93). There may be fitting nubs on the '86-87 carbs, one per tube — one nub fits into carb #1 and one into #4 (pink arrow). Note: 1990-97 have no fitting nubs.

Those old, hardened fuel lines will make installation more difficult and really should be replaced. Now's your chance. If the fuel lines are reluctant to come off the plastic tubes, warm them with hot water.

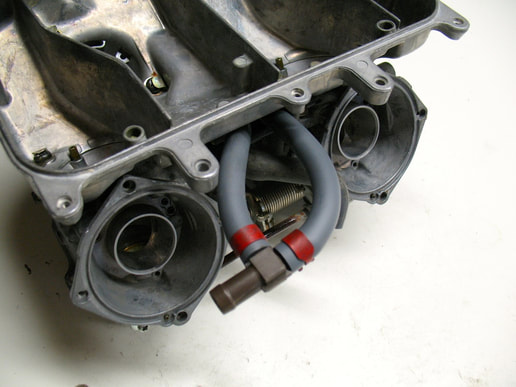

The two black air vent tubes will have fallen free, just let them hang free till installation. Note: 1990-97 have four black vent tubes. I reuse the vent tubes' o-rings as they're not critical seals.

Those old, hardened fuel lines will make installation more difficult and really should be replaced. Now's your chance. If the fuel lines are reluctant to come off the plastic tubes, warm them with hot water.

The two black air vent tubes will have fallen free, just let them hang free till installation. Note: 1990-97 have four black vent tubes. I reuse the vent tubes' o-rings as they're not critical seals.

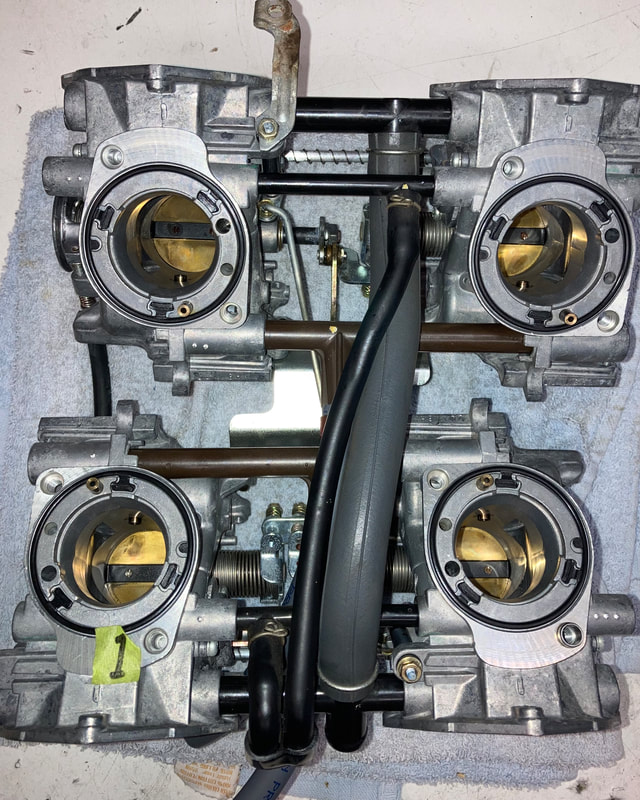

Remove the old o-rings, clean the grooves and install the new.

I now take a moment to clean the holes where the o-rings will seat with a bit of electronic cleaner (not brake solvent) and small brush, taking care to avoid any debris going into the carbs. If your carbs are disassembled like those in the photo, just blow air or cleaner into the threaded float valve hole visible at the upper left to flush this passage and ensure there's no gunk left behind.

We're ready to reassemble!

We're ready to reassemble!

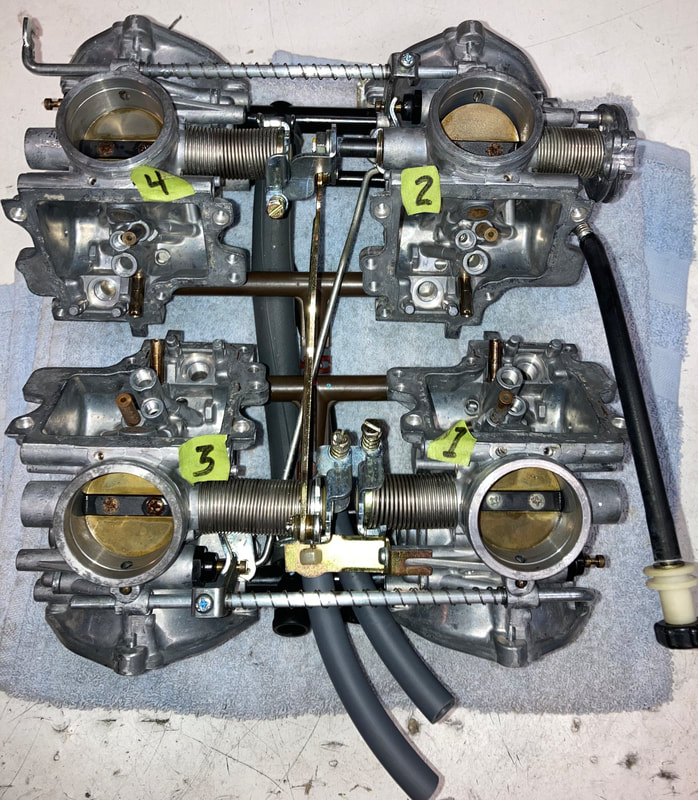

Reassembly, as they say, is the reverse of removal. Fit the fuel lines onto their respective fuel tubes — the shorter line connects to the #1/3 tube and the longer to the #2/4 tube, then thread them through the carb rack the same way they were removed (you took notes, right?). There's reference photos at the end of this post.

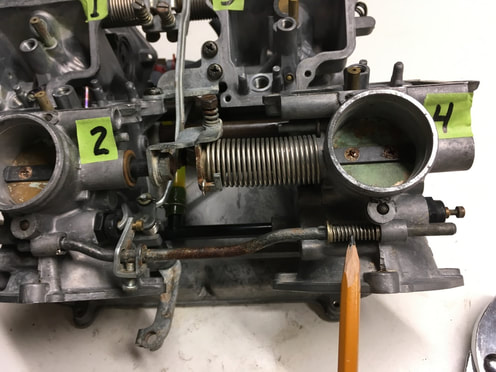

Fitting all the tubes and linkages back together is a bit like herding cats, but it can be done. Coat the new o-rings with a bit of oil or grease and fit #1/3 tube into place followed by #2/4, remembering that the locating nubs fit into carbs #1 & 4 ('86-87). The choke shaft will have fallen free of #1 & #4, so be sure it and its spring (the pencil is pointing to it) are back in place before mounting #1 & #4 on the plenum ('86-87) — '90-97 choke shafts can be installed later when the carbs are together. When all the fuel and vent tubes are lined up, work all the carbs back into place and fit onto their respective plenum mounting dowels ('86-93). For the '94-97 insert the three long locating dowels to hold everything in place — these should slip into place easily if everything is lined up. Don't forget the large o-rings between each carb and plenum — make sure they're back in their grooves.

None of this requires force. If you find yourself reaching for a hammer, take a breath and figure out why. It's a three dimensional puzzle, but it does fit back together.

Fitting all the tubes and linkages back together is a bit like herding cats, but it can be done. Coat the new o-rings with a bit of oil or grease and fit #1/3 tube into place followed by #2/4, remembering that the locating nubs fit into carbs #1 & 4 ('86-87). The choke shaft will have fallen free of #1 & #4, so be sure it and its spring (the pencil is pointing to it) are back in place before mounting #1 & #4 on the plenum ('86-87) — '90-97 choke shafts can be installed later when the carbs are together. When all the fuel and vent tubes are lined up, work all the carbs back into place and fit onto their respective plenum mounting dowels ('86-93). For the '94-97 insert the three long locating dowels to hold everything in place — these should slip into place easily if everything is lined up. Don't forget the large o-rings between each carb and plenum — make sure they're back in their grooves.

None of this requires force. If you find yourself reaching for a hammer, take a breath and figure out why. It's a three dimensional puzzle, but it does fit back together.

When everything's back in place, hold the whole affair together while carefully righting the carb rack and loosely reinstall the plenum screws, side screws or bolts, and then the center bracket on the underside ('86-93) — again, they should all go in and bottom easily if everything is lined up. The velocity tubes on the 1990-97 fit under the plenum and into slots in the carb bodies — take care to line up all four tubes before snugging the screws down. Once all the screws/bolts are in place, tighten them up. Flip the rack upside down and reinstall the missing shaft and sync springs (be careful, these will try to pop out and escape across the room). On the '86-93 the larger shaft spring goes between #2/4 and the smaller between #1/3 — for '94-97 the longer goes between #2/4, the shorter between #1/3. During the reassembly process, you should be continually checking that the throttle and choke mechanisms are free and correct. There should be no binding.

Apply a bit of oil to the pivot and sliding areas of the choke and throttle linkages. Visually check that all the carbs are seated square and flush, and that the carb-to-plenum o-rings haven't become dislodged.

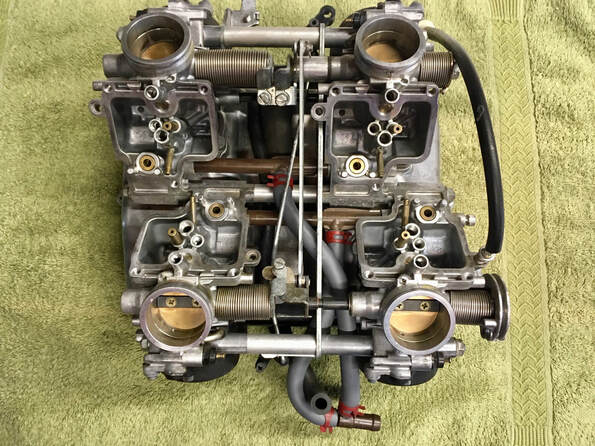

Install the fuel lines onto the "T" fitting. When installed correctly, the different length replacement fuel lines will look like this, facing carb #1 just like from the factory. If using my replacement lines, you may want to shorten one or both slightly to get the correct curvature of the fuel lines without crimping.

FOR REFERENCE:

(Right) Here's a look at the '94-97 carb rack with new fuel lines installed showing the correct routing and the "T" fitting.

(Below) Here are top and bottom views of the '90-93 rack showing correct routing of the lines.

(Right) Here's a look at the '94-97 carb rack with new fuel lines installed showing the correct routing and the "T" fitting.

(Below) Here are top and bottom views of the '90-93 rack showing correct routing of the lines.

(Right) Here's a reference photo for the '86-87. On this carb set the vent line happens to be green colored so gives a good reference as to how the grey fuel lines should be routed. Here we're looking upside-down between carbs #1 & 3.

After all this fiddling about, the carbs will need to be sync'd on the running bike. Syncing is an important step on any multi-cylinder, multi-carb engine and shouldn't be ignored.

TIP: install the sync fittings onto the engine intake manifolds before installing the carbs.

TIP: Check the carb set for leaks before mounting on the engine; see tutorial #20, Carburetor Installation.

Congratulations, you're done!

Your carburetors thank you.

After all this fiddling about, the carbs will need to be sync'd on the running bike. Syncing is an important step on any multi-cylinder, multi-carb engine and shouldn't be ignored.

TIP: install the sync fittings onto the engine intake manifolds before installing the carbs.

TIP: Check the carb set for leaks before mounting on the engine; see tutorial #20, Carburetor Installation.

Congratulations, you're done!

Your carburetors thank you.

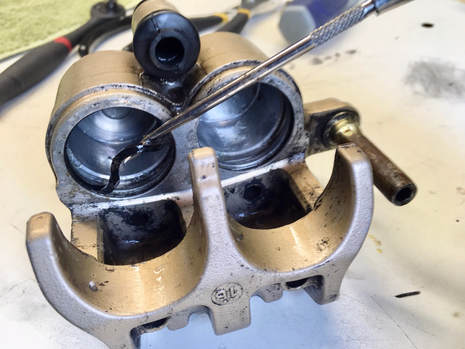

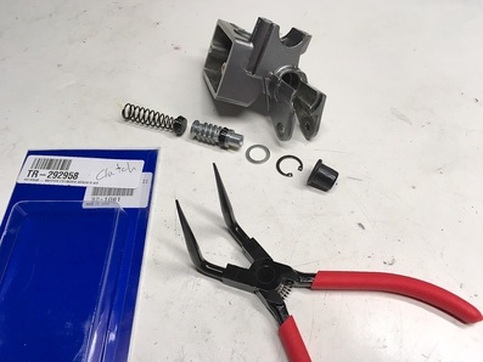

2. Rear Caliper Sleeve Replacement ('86-87)

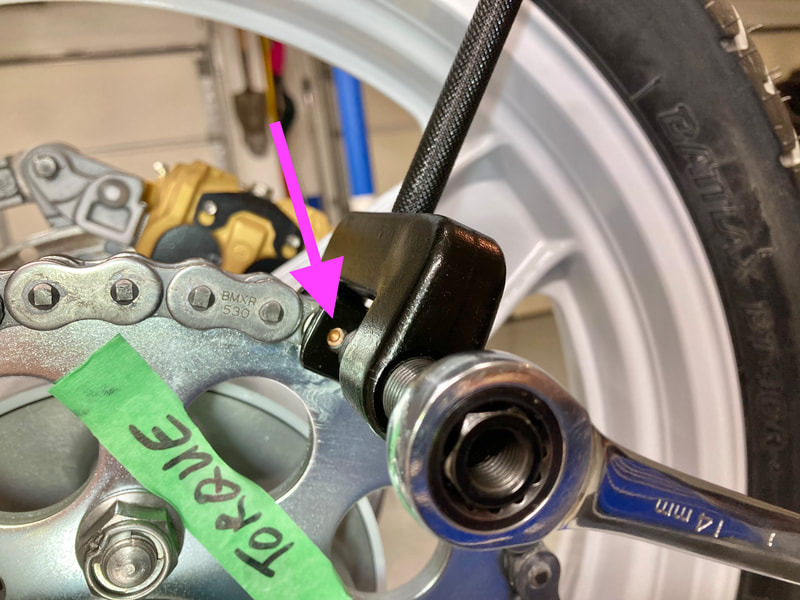

On nearly all of my projects I come across an all-to-common issue — the lower mounting point on the rear caliper of the 2d-gen model.

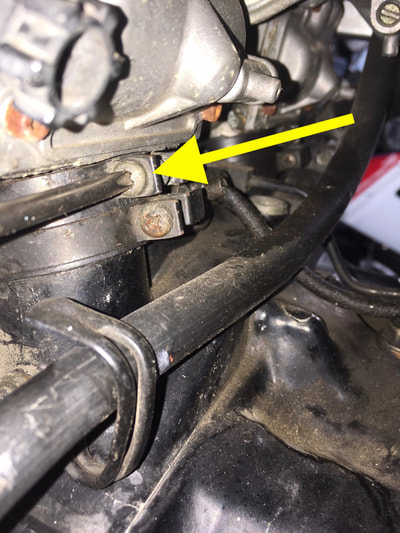

The mount consists of this "sleeve," as Honda calls it, which is required to slide slightly to & fro in its boss as the brake is cycled. Trouble is, this particular pin is usually severely corroded and often frozen in place. The brake will still function but at a fraction of its potential. It seems well-protected by two tightly-fitted rubber boots (shown in background) but still suffers from its location at the bottom of the caliper.

The mount consists of this "sleeve," as Honda calls it, which is required to slide slightly to & fro in its boss as the brake is cycled. Trouble is, this particular pin is usually severely corroded and often frozen in place. The brake will still function but at a fraction of its potential. It seems well-protected by two tightly-fitted rubber boots (shown in background) but still suffers from its location at the bottom of the caliper.

This is the result of the sleeve being frozen in place by corrosion. The inboard brake pad isn't allowed to slide freely, resulting in only the upper portion making contact with the disc. Note the bevelled profile of the inboard pad. These pads are junk.

Fortunately, the sleeve and boots are still available from Honda. The sleeves retail for about $12, the boots $4.

Often, freeing the sleeve from the caliper is difficult — this one was soaked overnight in penetrating fluid and then twisted loose. I've also taken these to a machine shop where they can press them out in a few minutes, often at no charge. The boots are often in reuseable condition.

Often, freeing the sleeve from the caliper is difficult — this one was soaked overnight in penetrating fluid and then twisted loose. I've also taken these to a machine shop where they can press them out in a few minutes, often at no charge. The boots are often in reuseable condition.

The bore itself typically only needs cleaning with a brass brush and flushing with brake cleaner. I then coat the bore with some silicone grease and reinstall the sleeve and seals — there's a trick to this; install one seal, push the sleeve all the way through from the opposite side, install the second seal then slide the sleeve back to the second seal, engaging the seals in the slider grooves.

I'm sure if these sleeves were serviced at each brake pad replacement or say, ten years, they'd remain in useable condition.

Job done!

I'm sure if these sleeves were serviced at each brake pad replacement or say, ten years, they'd remain in useable condition.

Job done!

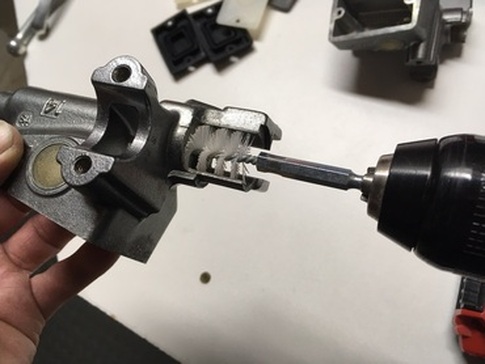

3. Master Cylinder Rebuild

Of all the systems on a vehicle, the brakes are a high-priority maintenance item. I always remove the complete braking systems, disassemble, clean and rebuild with fresh parts. Here, I'll tackle the clutch and front brake master cylinders.

All too often when I open up the master cylinders this is what lay in wait. This situation is very common with my projects and is due to nothing more than neglect. Brake fluid should be flushed every two years, and this is the long-term result of ignoring that maintenance item.

All too often when I open up the master cylinders this is what lay in wait. This situation is very common with my projects and is due to nothing more than neglect. Brake fluid should be flushed every two years, and this is the long-term result of ignoring that maintenance item.

I don't know how that solidified gunk forms, but fortunately it cleans up with a straightforward sudsy washing.

Both of these master cylinders will require a complete rebuild. That involves new seals and replacing the aged sight glasses.

I clean the bore with solvent and a plastic rotary brush. If the bore then passes a visual inspection I move on with the sight glass repair before installing the new seals — I don't want to risk debris from the old sight glass contaminating the seals. (Sight glass replacement is covered in the next tutorial)

Here's the rebuild kit ready for installation. Coat the parts with Red Rubber Grease or brake fluid and carefully install into the bore in the order shown. Pictured is the clutch master from an '86-87 VFR.

I hold the assembled plunger down in the bore (against the spring pressure) with a screwdriver while inserting the circlip, verifying that the circlip is fully seated. The K&L bent-tip snap ring pliers makes this juggling act a much smoother operation.

Next up are the levers. Motion Pro and probably others make complete reproduction levers for the VFR, but there's nothing like the originals if they can be saved.

A thorough inspection is called for with these old parts and their unknown history. While looking over the brake lever I discovered this crack on the underside. It obviously resulted from a crash or tip-over. No question that this one goes into the trash bin.

Who knew these adjustable levers have so many parts?

After a thorough cleaning, de-rusting and polishing, I carefully reassemble the levers with a touch of silicone or lithium grease on all the rotating parts. Fresh stainless steel reservoir screws are a finishing touch.

Once the sight glass lenses are installed, these reservoirs are ready for the next 30 years.

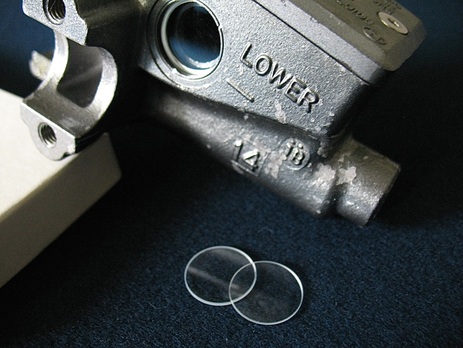

4. Sight Glass Replacement For Brake & Clutch Master Cylinders

The OEM master cylinder sight glass lenses are made of some sort of plastic. After 30+ years of exposure to brake fluid and sunlight they've become cloudy, brittle and even opaque. This defeats their purpose as a sight glass to check the fluid level and in the worst case can result in leakage — brake fluid makes a very effective paint remover as it drips onto your nice fuel tank. Time to fix it.

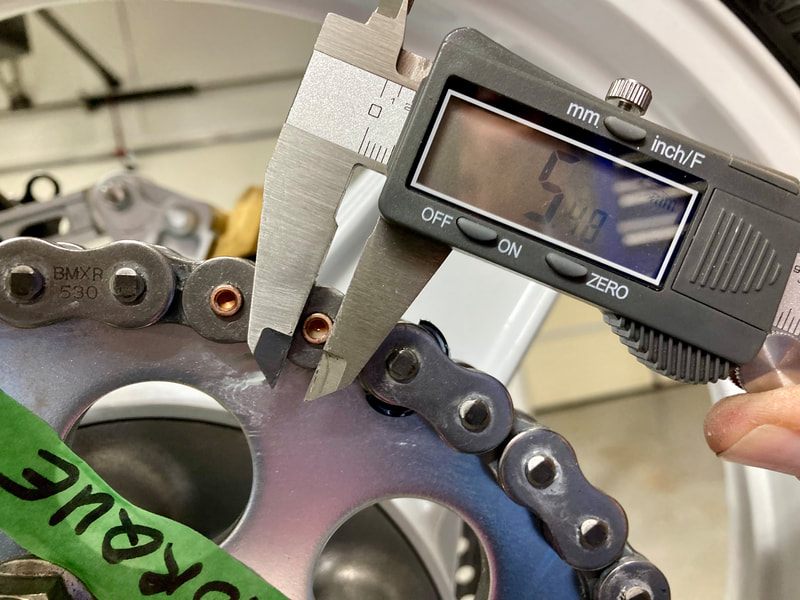

Replacement lenses can be sourced inexpensively through eBay or Amazon. To determine the correct size lens, remove your old lens, backing plate and o-ring. Using a sliding caliper, measure the hole diameter that the lens will be sitting on. Order a lens sized to just fit into the hole but still rest on the base ridge, i.e. 16mm. I recommend lenses made of glass.

Here's my replacement process:

Replacement lenses can be sourced inexpensively through eBay or Amazon. To determine the correct size lens, remove your old lens, backing plate and o-ring. Using a sliding caliper, measure the hole diameter that the lens will be sitting on. Order a lens sized to just fit into the hole but still rest on the base ridge, i.e. 16mm. I recommend lenses made of glass.

Here's my replacement process:

I begin with the demolition of the old plastic window. A tap with a small screwdriver from the inside starts the process. Then, using a larger flat-blade screwdriver I pry around the perimeter from the outside, working my around.

Sometimes they come out pretty cleanly, as here, and sometimes not…keep at it, they will eventually be defeated.

I also remove the metal backing plate and its o-ring.

(Below) The idea is to get to the ridge at the bottom of the hole (pink arrow). In the case of this master, that ridge has a 15mm hole diameter, while the main casting hole diameter is 16mm, so that's the maximum size I'll be able to fit into the recess. However, there's a second ridge (yellow arrow) which won't allow the 16mm lens to drop into place. I gently grind that away with a sanding drum mounted on the Dremel until I can just slip the 16mm lens into place.

After a final cleaning of the lens and it's seating groove with acetone or similar, I fill the groove with adhesive, then stick the lens on a finger tip (using rolled-over masking tape) and carefully apply adhesive around the perimeter.

I use good ol' JB Weld, which claims to be impervious to most chemicals. It also drys to a dark gray, which works well here.

Carefully set the lens in place to fully seat it in the adhesive but not so hard as to squeeze the adhesive too thinly.

I allow the adhesive to fully cure for a day or two. Expect some residual adhesive to show, but overall a practical repair.

Job done!

5. Carburetor Bowl Gasket Replacement

The combination of time and modern fuels have conspired to make the replacement of the OEM carburetor float bowl gaskets an eventual necessity. This operation is straightforward but does require the removal of the carb rack (see tutorial #17, Carburetor Removal), so plan a full afternoon in the garage. In this tutorial I'm picturing the '86-87 carbs.

The good news is that we now have accessibility to modern, inexpensive replacement gaskets in the form of VITON o-rings. These o-rings are superior to the OEM gaskets, especially in their care-free attitude toward ethanol. They're available on the "Products" page or my eBay listing.

If your carbs are leaking after storage this is a likely culprit (along with the fuel tube o-rings). I sometimes find this mess with my projects (right), where a desperate previous owner has gooped some sort of sealer on the gasket to try to seal it — please don't do this.

The good news is that we now have accessibility to modern, inexpensive replacement gaskets in the form of VITON o-rings. These o-rings are superior to the OEM gaskets, especially in their care-free attitude toward ethanol. They're available on the "Products" page or my eBay listing.

If your carbs are leaking after storage this is a likely culprit (along with the fuel tube o-rings). I sometimes find this mess with my projects (right), where a desperate previous owner has gooped some sort of sealer on the gasket to try to seal it — please don't do this.

The dried and brittle old gasket will likely look like this.

Both the gasket groove in the bowl and the sealing surface on the carb body will need to be cleaned. I use a tiny screwdriver blade or dental pick to scrape out most of the hardened residual cement from the bowl groove. Then a brass brushing followed by a wash and rinse.

Next I tackle the carb surface. Using a kitchen scrub pad, I clean the sealing surface of any residual contaminates, being mindful of getting dirt into the carb bowl. I then gently blow out the bowl area with compressed air or by blowing through a soda straw. The floats are easily removable if you want more accessibility to the bowl.

You want the sealing surfaces to look like this.

The o-ring gaskets are simply pressed into place and the bowl screwed back onto the carb (don't overtighten the screws). If the gaskets are reluctant to stay in place (especially true with the '94-97 carbs) a bit of grease or small dabs of gasket cement will help hold them in place during installation. Avoid the temptation to use RTV or gasket sealer — it just makes a mess and can find its way into the carbs, causing future problems.

TIP: While your bowl covers are off, check the float height adjustments ('86-93).

A short video is provided below…..

TIP: While your bowl covers are off, check the float height adjustments ('86-93).

A short video is provided below…..

6. Fuel Tank Sealing

My trials and tribulations with VFR projects have included lots of fuel tanks in varying states of...ahh...despair. They're all the same relative age, so their condition is a reflection of how they've been cared for over the decades. I've come across tanks which look great on the ouside but heavily rusted internally, and just the opposite. But, like a Realtor likes to say about waterfront property, "they ain't makin' any more," so these tanks are worth saving, and that's where tank sealant comes in.

My choice for do-it-yourself tank sealant is Caswell"s motorcycle sealing kit. This kit runs $40 for clear and $55 for colored. Both are a 2-part epoxy with some pretty fancy chemists' terms associated with it (i.e. "phenol novolac is more thixotropic") but the bottom line is that Caswell claims it sticks better, even to uneven rusty surfaces and is resistant to anything short of a nuclear detonation. It will bridge and seal up actual gaps and is pretty easy to work with. Pictured above is another product I like to use on tanks with a salvageable exterior finish; Seal Mask. This pink liquid brushes on the painted finish and protects during the cleaning and application process. Pretty amazing stuff, 'cause it washes off with only clear water when finished. Caswell provides written instructions with the kit and on their website.

My choice for do-it-yourself tank sealant is Caswell"s motorcycle sealing kit. This kit runs $40 for clear and $55 for colored. Both are a 2-part epoxy with some pretty fancy chemists' terms associated with it (i.e. "phenol novolac is more thixotropic") but the bottom line is that Caswell claims it sticks better, even to uneven rusty surfaces and is resistant to anything short of a nuclear detonation. It will bridge and seal up actual gaps and is pretty easy to work with. Pictured above is another product I like to use on tanks with a salvageable exterior finish; Seal Mask. This pink liquid brushes on the painted finish and protects during the cleaning and application process. Pretty amazing stuff, 'cause it washes off with only clear water when finished. Caswell provides written instructions with the kit and on their website.

If the paint is to be saved, I first brush on one or two coats of Seal Mask, which dries in about 30 minutes to a thick plastic film. Caswell also suggests taping plastic and aluminum foil over the tank, but I've not found that necessary if you're careful. Or, use that approach in lieu of Seal Mask.

Our first task is to prep the inside of the tank as best we can. Remove the petcock; you'll need to "back blow" compressed air through the openings after sealing. I install the lower fuel level sensor with its rubber gasket and tape the top filler hole or just close the filler if it's still in place. Using acetone, I slosh about a pint of it around the interior with a double handful of small drywall screws, drain out the bottom hole, and repeat as needed.

This photos shows what typically comes out of a rusty tank. The putrid smell of rancid gas can permeate a garage for a few days — be warned. When I'm happy with the cleaning operation I open up both holes and allow the tank to completely dry for a couple of days.

Next we need to mix the 2-part epoxy in a plastic container. Working time is dependent on air temperature, but basically be ready to pour into the tank immediately after mixing.

Shown here is the clear sealant.

Pour the very thick mixture into the filler opening (with the bottom opening taped over), tape the filler opening, and slowly rotate the tank to distribute on all surfaces. When I'm satisfied that everything's coated, uncover the lower hole and prop the tank level, a few inches off the table surface, allowing it to drain for a couple of hours. I place a plastic grocery bag or some wax paper under the the opening to allow the drained glob to solidify on it. Immediately after beginning the drain operation blow compressed air into the fuel pickup tubes (at the petcock) to clear potentially clogged pickup screens inside the tank — don't skip this step. After about an hour, I'll take a sharp blade and cut off any drips around the drain hole. Caswell suggests allowing the tank to sit a few days, undisturbed, to cure the epoxy.

Shown here is the clear sealant.

Pour the very thick mixture into the filler opening (with the bottom opening taped over), tape the filler opening, and slowly rotate the tank to distribute on all surfaces. When I'm satisfied that everything's coated, uncover the lower hole and prop the tank level, a few inches off the table surface, allowing it to drain for a couple of hours. I place a plastic grocery bag or some wax paper under the the opening to allow the drained glob to solidify on it. Immediately after beginning the drain operation blow compressed air into the fuel pickup tubes (at the petcock) to clear potentially clogged pickup screens inside the tank — don't skip this step. After about an hour, I'll take a sharp blade and cut off any drips around the drain hole. Caswell suggests allowing the tank to sit a few days, undisturbed, to cure the epoxy.

Here's a look at a cured tank interior, in grey.

After curing, peel away the Seal Mask, or just dissolve with water.

Reassemble your refurbished fuel tank and add gas.

Job done!

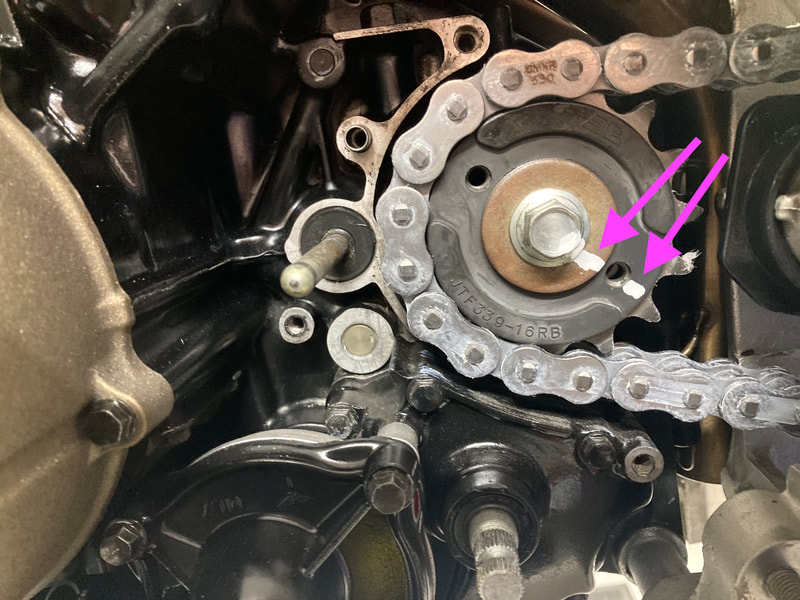

7. Screw-type Master Link Install

These high-performance bikes' drive chains don't, or shouldn't, use a clip-type master link, but instead require a riveted master. Assembling a master link requires the right touch when pressing (riveting) the master pins — not too much, not too little.

Here's a different approach on a master link install from manufacturer EK.

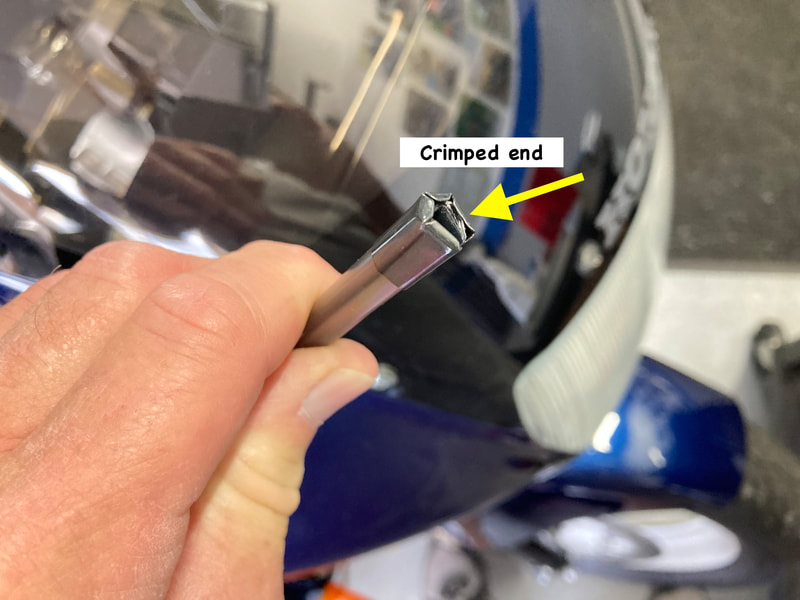

They call this a screw-type connecting link, and the objective is to take the guess work out of your master link installation. After assembling the plates, these two nuts are alternately screwed down till they bottom, which gives the correct "squish." They're then backed off to the narrowed portion of the shaft and......

.....snapped off with a pliers. I grind down the nubs a bit for aesthetics.

This is a easy and sure-fire alternative to riveting master links. Especially handy if you only do this occasionally and don't have access to a chain breaking/riveting tool.

Tip: If you don't have a chain breaker, the chain can simply by cut through with a cut-off tool or hacksaw, assuming you're not reusing that chain.

A pin can also be removed by grinding down one of the pin faces and, using a hammer and drift, push the rivet pin out the backside of the plate.

A pin can also be removed by grinding down one of the pin faces and, using a hammer and drift, push the rivet pin out the backside of the plate.

8. Reinstalling Mufflers — Tip

While preparing an OEM muffler set for installation on Project 18 I devised a way to make my life just a little easier. These old systems can be a real bear to remove, and even harder to reinstall. Something that would really help is to expand the female joint before sliding onto the header pipes.

Here's one of the pipes in question, and what happened to the old exhaust gasket when removing it.

Here's one of the pipes in question, and what happened to the old exhaust gasket when removing it.

This is my homemade tool, which is the same black gas pipe I use to drive steering head bearings into place. The cut threads on these pipes are slightly tapered, so tapping the pipe into the muffler opening gently expands the opening.

Here's a fresh gasket in place in the expanded opening. When installing the mufflers, I slip the new gaskets onto the exhaust pipes and slide the mufflers in place. Even with the expanded openings this can be a pushing and shoving match. It's never an easy chore.

The clamps are right & left specific, so be sure to get them oriented correctly before installing the mufflers.

With everything test fitted, the system can be removed, the black muffler pipes sanded and painted, and they'll slip into place with much less muscle.

Job done!

9. Fork Leg Refinishing

The lower fork legs on our old bikes are made of aluminum alloy. To preserve their showroom shine the factory applied clearcoat, but decades of stone chips and neglect have them looking like a bad case of acne. After a thorough cleaning I set to refinishing these aluminum lower fork legs.

My solution is to first strip the clear-coat with chemical stripper followed by a wet-sanding with 320-grit, then 800-grit. The 320 will remove the pockmarks of corrosion and the 800 eliminates sanding marks.

For some parts I'll go with even finer sanding, up to 3000, but I liked the dull sheen that the 800-grit provided on these legs — very factory-like. Here's the sanded part ready for polish.

It's easy to get carried away with aluminum polishing but in this case I wanted just a bit of shine, so a single pass with Mother's Mag & Aluminum Polish did the trick.

To try and preserve the finish we could have these parts powder coated with clearcoat, but I've chosen to leave them bare and remember to give them a hand polishing once a year. They live in a harsh environment where stone chipping is a fact of life, but they're very easy to access for a quick cleaning/polishing.

Job done!

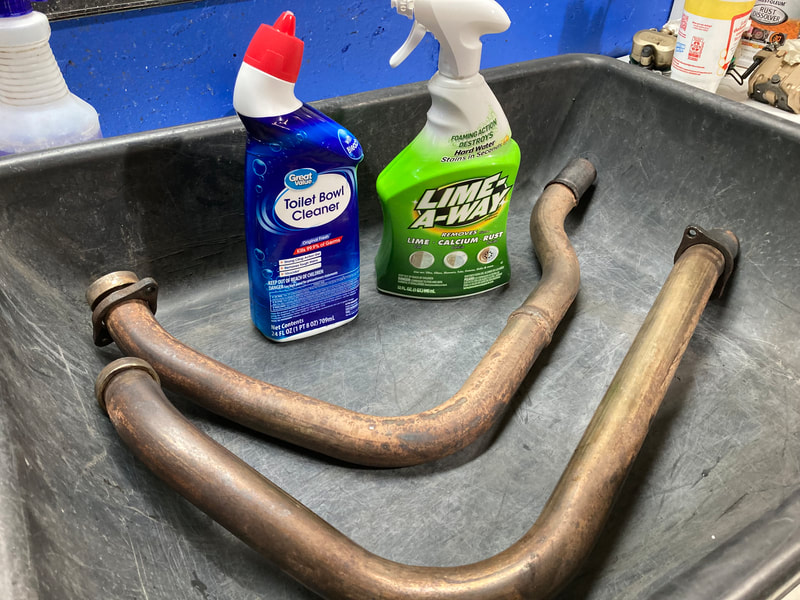

10. Muffler Refurbishing - OEM

To my eye, the OEM mufflers fitted to the U.S.-spec '86-87 VFRs are made of steel with some sort of thin coating applied to the exterior (anodizing?), similar to ceramic coating but resembling stainless steel.

In any case, if left to the elements, the mufflers will oxidize (rust) and this is how it begins. Fortunately, if caught in time, the pipe can be saved.

Below, I'm applying Turtle Wax Chrome Polish & Rust Remover with a non-scratch kitchen scrub pad. It pays to be gentle here and let the polish do its magic, which is to help remove the surface rust spots. I apply plenty, keep it wet, and just kind of massage it around the piece for about ten minutes.

Let it dry to a haze and buff out with a soft cloth. The deeper corrosion spots will still leave a shadow, but overall the metal is now very presentable. Repeat once per year to prevent further damage.

In any case, if left to the elements, the mufflers will oxidize (rust) and this is how it begins. Fortunately, if caught in time, the pipe can be saved.

Below, I'm applying Turtle Wax Chrome Polish & Rust Remover with a non-scratch kitchen scrub pad. It pays to be gentle here and let the polish do its magic, which is to help remove the surface rust spots. I apply plenty, keep it wet, and just kind of massage it around the piece for about ten minutes.

Let it dry to a haze and buff out with a soft cloth. The deeper corrosion spots will still leave a shadow, but overall the metal is now very presentable. Repeat once per year to prevent further damage.

11. Muffler Refurbishing - Yoshimura

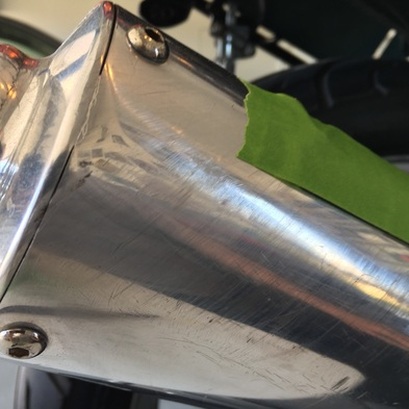

Mufflers make for effective crash bars when a spill occurs. Even an otherwise harmless tip-over will usually leave a mark on our exposed mufflers. Aftermarket cans, like this Yoshimura mounted on an '87 VFR700 F2, are often made of soft aluminum — this is good and bad: The metal damages easily but can often be repaired with some gentle persuading.

Here's a look at some rash suffered along the entire length of the muffler during a 30-mph slide. The metal is gouged and scraped. I won't be able to bring back depressed or dented areas, but I can help the other damage. The green tape is covering the Yoshimura badge to protect it during the next steps.

Here's a look at some rash suffered along the entire length of the muffler during a 30-mph slide. The metal is gouged and scraped. I won't be able to bring back depressed or dented areas, but I can help the other damage. The green tape is covering the Yoshimura badge to protect it during the next steps.

I begin with a heavy rasp to knock down the deep gouges. The blue on the file is chalk — rubbing chalk on the file keeps the aluminum filings from clogging the file. I'll follow with a finer file.

Switching to wet/dry sandpaper, I begin with 100-grit on the filed sections, and 400-grit on the scratches, then move progressively finer.

I'll end with 5000-grit which makes the final polishing a breeze.

Here, the final sanding shows a smooth but cloudy finish.

Aluminum polish applied by hand is all that's necessary to bring out the shine. The entire process took about an hour. Good thing aluminum is so forgiving.

12. Decal Removal (No Mar)

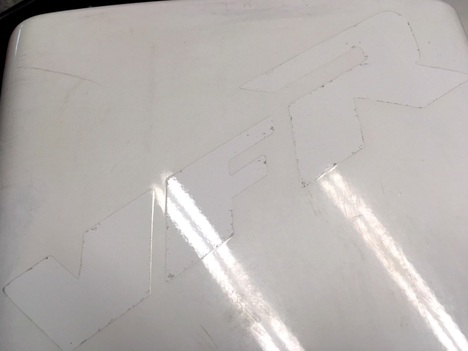

As our bikes mature with the passing years, I'm finding — more often than I'd like — that I'm forced to repaint the bodywork on my projects. The first step for any paint job is to thoroughly clean the panels followed by removing the old decals. Decal stripping be accomplished with machine sanding but that's gonna' leave a mark on the plastic parts, so I choose finesse over brute force.

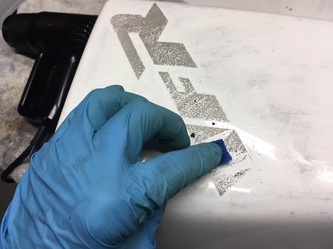

I first determine if the decal has been clearcoated. If so, I go around the edge of the decal with a palm sander to provide a clean edge. After a gentle application from the heat gun on low setting, I begin scraping with a fresh plastic razor blade. Unlike a steel razor, the plastic blade won't gouge the plastic. I can only progress about one to two inches before needing more heat — we just need the decal warmed so proceed carefully, the ABS can deform with too much heat.

I first determine if the decal has been clearcoated. If so, I go around the edge of the decal with a palm sander to provide a clean edge. After a gentle application from the heat gun on low setting, I begin scraping with a fresh plastic razor blade. Unlike a steel razor, the plastic blade won't gouge the plastic. I can only progress about one to two inches before needing more heat — we just need the decal warmed so proceed carefully, the ABS can deform with too much heat.

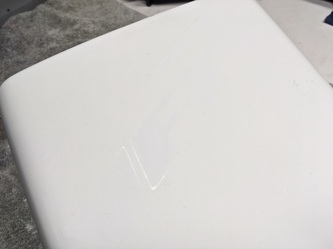

Sometimes the adhesive will remove almost completely, but more likely most will be left behind, as pictured here.

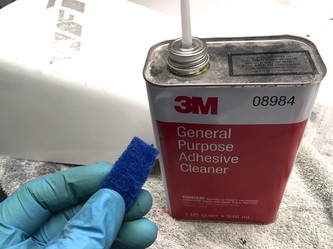

Not a problem. Using a strip of non-scuff kitchen pad, I soak a section of adhesive with 3M General Purpose Adhesive Cleaner for about 30 seconds and gently scrape the residue with a fresh plastic blade (I buy them in packs of 100). Repeat as necessary and finish with a final wipe with a clean paper towel wetted with adhesive cleaner.

We're left with a nice clean surface, but with a distinct outline where the clearcoat edge was. This needs to be removed or it will show under the new paint.

So, my final step is a general sanding of the entire piece in preparation for paint (below, left). For this I use wet-dry 320-grit paper with a little extra attention to the decal outline.

This cowl took about 30 minutes to this point and I'll spend four or five hours removing all the bike's decals. From here I'll deal with any plastic repair and/or bodywork required.

So, my final step is a general sanding of the entire piece in preparation for paint (below, left). For this I use wet-dry 320-grit paper with a little extra attention to the decal outline.

This cowl took about 30 minutes to this point and I'll spend four or five hours removing all the bike's decals. From here I'll deal with any plastic repair and/or bodywork required.

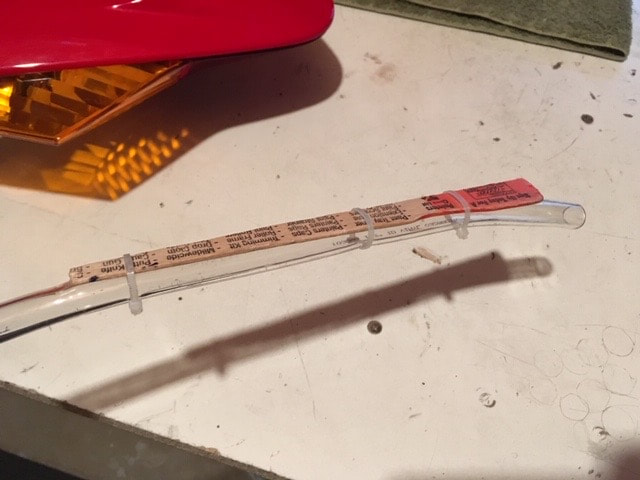

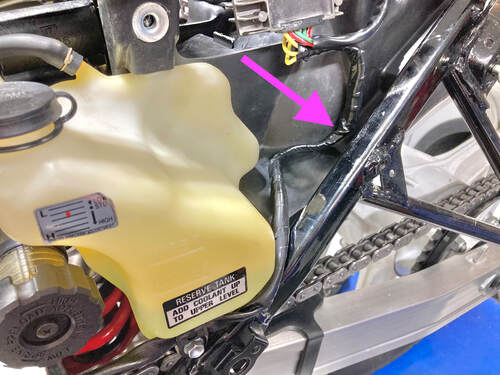

13. Coolant Hose Generic Replacement

The coolant hoses for the second- through fourth-generation VFRs are no longer available from Honda. A high-quality replacement set is offered from Samco (samcosport.com) but at the equally high price of $170 ('86-87). A Samco set is pictured at right. In 2022 I partnered with AS3 (as3performance.com) in the UK, convincing them to include a kit for the RC24/26 in their catalog.

I've never come across generic replacements for the two large radiator hoses, but the small ones, two for the '86-87 and three for the '90-97, can be sourced locally. These small hoses live in a harsh environment and I get peace of mind by replacing them on my projects. They're located under the carb set and under the kick stand area. Before removing the various hoses, note how the hose clamps are oriented and replace in the same direction.

I've never come across generic replacements for the two large radiator hoses, but the small ones, two for the '86-87 and three for the '90-97, can be sourced locally. These small hoses live in a harsh environment and I get peace of mind by replacing them on my projects. They're located under the carb set and under the kick stand area. Before removing the various hoses, note how the hose clamps are oriented and replace in the same direction.

We're using a donor hose for the upper hoses under the carb set — Gates #19746, available locally, Amazon or eBay. Pictured are the two original upper hoses from the third- and fourth-gen bikes.

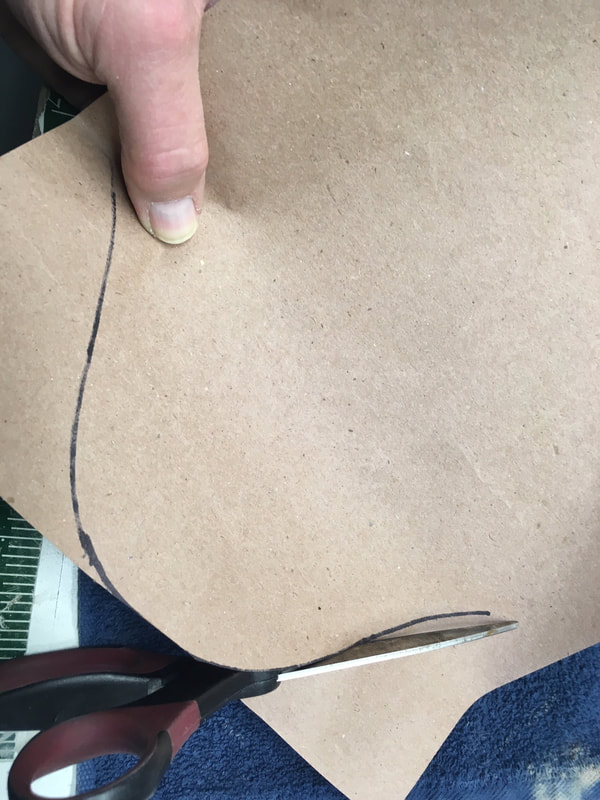

The procedure is to mark the new hose using the old sections, cut and install.

The procedure is to mark the new hose using the old sections, cut and install.

Here they are as installed on the '90-97.

And here's the single hose on the '86-87.

The lower hose is a 22mm (7/8") I.D. piece cut from a straight section of silicon coolant hose which I've sourced from Amazon. Replacement is straight-forward, but getting the old hose off can be a workout, made difficult as there's only about 20mm of space to remove/install a 70mm length of hose. I use my handy ARES hose removal tool (lower photo) and work my way around the hose ends.

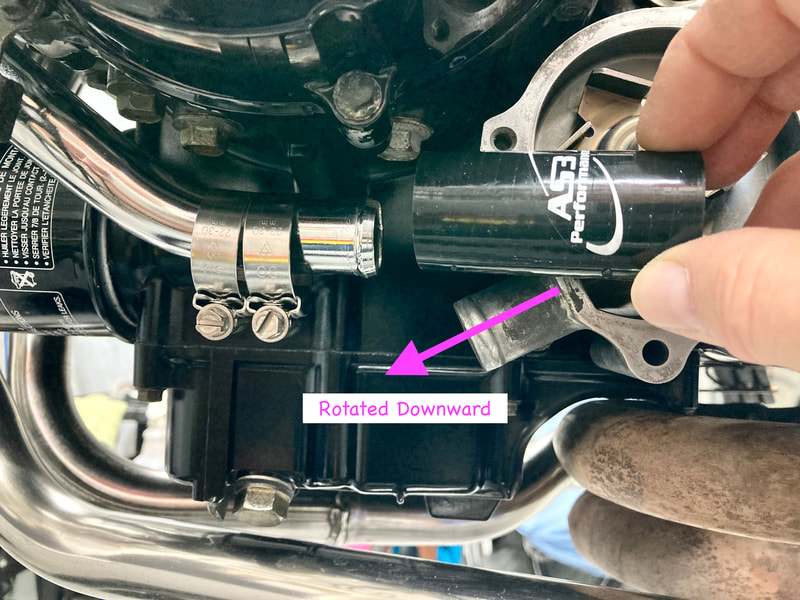

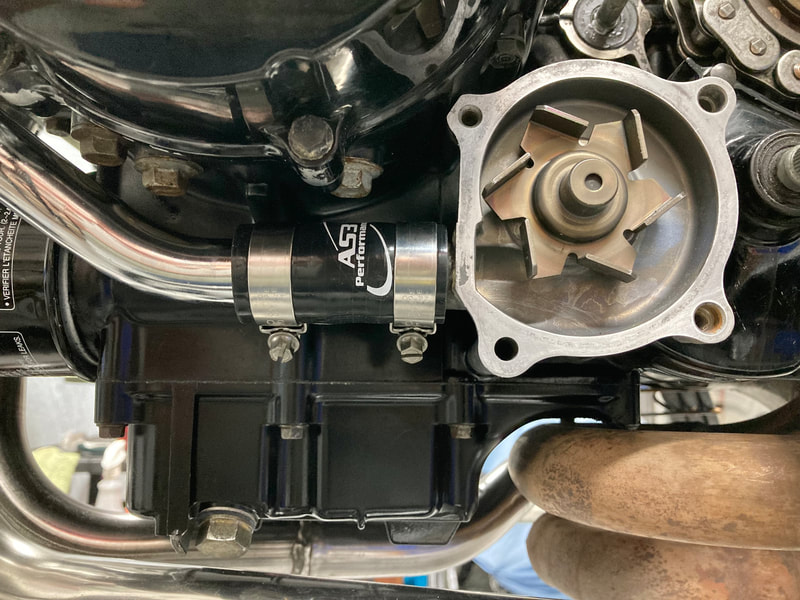

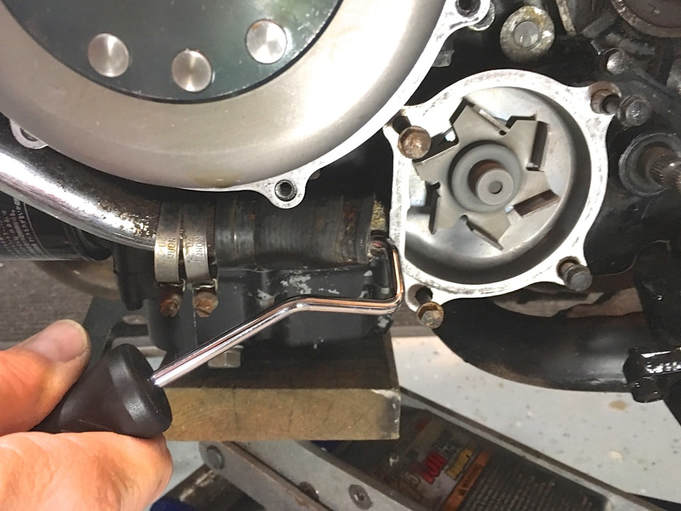

(Below) Here's a trick I use: Remove the water pump cover (this should be done in any case to inspect the water pump impeller blades). Pull outward slightly on the pump housing which allows the housing to rotate — this provides much more room to remove/install the hose. Slide the hose onto the chrome pipe, rotate the housing back into place, and slide the hose back onto the housing nipple. Before tightening the hose clamps, be sure to align the pump housing's bolt holes. Note: The pump housing can be entirely removed by pulling straight outward, but be sure the oil sump is drained down about a quart or oil will exit through the mounting hole. If you choose to remove the cover and/or pump you'll want to have new o-rings on hand — one for each — available from Honda.

If you leave the water pump in place, it helps to unbolt the hold-down bolt for the chrome coolant pipe coming down from the upper engine area and work the old hose backward onto the chrome pipe and force it off through the gap. You can also cut the hose into smaller pieces to remove it.

(Below) Here's a trick I use: Remove the water pump cover (this should be done in any case to inspect the water pump impeller blades). Pull outward slightly on the pump housing which allows the housing to rotate — this provides much more room to remove/install the hose. Slide the hose onto the chrome pipe, rotate the housing back into place, and slide the hose back onto the housing nipple. Before tightening the hose clamps, be sure to align the pump housing's bolt holes. Note: The pump housing can be entirely removed by pulling straight outward, but be sure the oil sump is drained down about a quart or oil will exit through the mounting hole. If you choose to remove the cover and/or pump you'll want to have new o-rings on hand — one for each — available from Honda.

If you leave the water pump in place, it helps to unbolt the hold-down bolt for the chrome coolant pipe coming down from the upper engine area and work the old hose backward onto the chrome pipe and force it off through the gap. You can also cut the hose into smaller pieces to remove it.

14. Reshaping A Chain Guard

In their effort to "add lightness," Honda began to use more plastic during the 1980s. One part that changed from heavy metal was the chain guard. Over time, however, the long and not very well supported piece tends to twist or warp and begins to look a little wonky. I've found that if the right amount of heat is applied judiciously these plastic parts can be massaged nearer to their original shape.

This chain guard was deformed near the rear and actually rubbing on the rear sprocket. Using a heat gun I gently warm the area that I think will help reshape the part and then hold it (with thick gloves, it gets hot!) as it cools. This takes several gentle attempts. Be careful, too much heat and the part can deform or even bubble till it's no longer useable.

This process can be done on the bench or while mounted on the bike.

This chain guard was deformed near the rear and actually rubbing on the rear sprocket. Using a heat gun I gently warm the area that I think will help reshape the part and then hold it (with thick gloves, it gets hot!) as it cools. This takes several gentle attempts. Be careful, too much heat and the part can deform or even bubble till it's no longer useable.

This process can be done on the bench or while mounted on the bike.

To bring back the original finish I lightly wet sand the chain guard and apply one or two coats of Griot's Bumper & Trim Reconditioner. This stuff works on all the black plastic parts, like the rear fender/license plate area. As an alternative for severely weathered plastic finishes, I paint the part with a plastic trim paint, like SEM Trim Black, available at body supply stores or Amazon.

15. Steering Head Bearing Replacement

When checking for steering bearing problems we're looking for roughness and especially a notchy feeling at the center point of the handlebar swing. Looseness can sometimes be dealt with by correctly adjusting the bearing tightness, but often as not the looseness has resulted in excessive wear to the bearings and their races.

These bikes were originally equipped with ball (roller) bearings, and there's nothing wrong with that approach in this application, but tapered bearings are an upgrade and should outlast the OEM bearings.

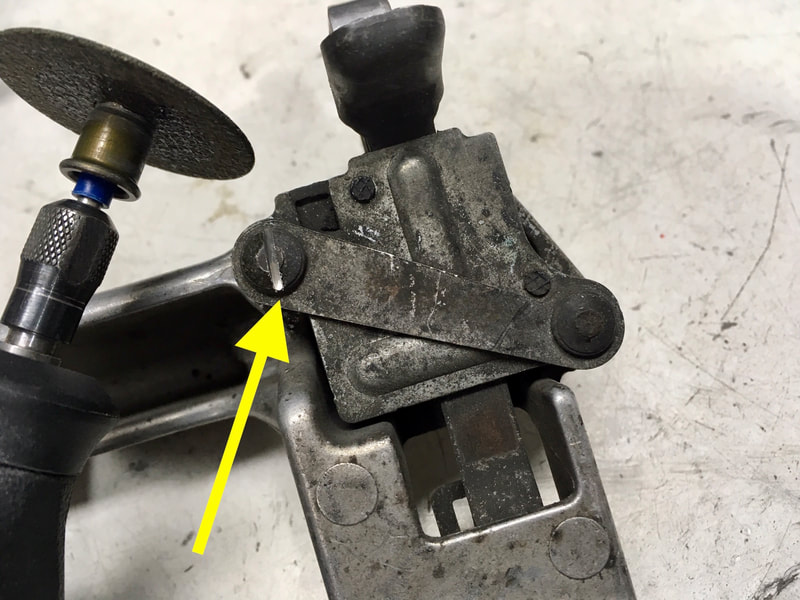

But how to remove and install the pressed-on lower bearing without the nice factory tools (or a handy machine shop equipped to remove and press the bearings)? Well, the old bearing inner race won't drive off, so I use a Dremel with a cut-off blade and very carefully slice the race with a diagonal cut, stopping just shy of cutting into the shaft itself. Right at that magical point the bearing race gives a little "bing" as it loosens its grip on the shaft — it can then be pried off with a screwdriver blade. In the photo above are (left to right) the new lower seal, the new bearing, the old inner race and the old outer race. I will use the old parts as adaptors to drive the new bearing in place.

These bikes were originally equipped with ball (roller) bearings, and there's nothing wrong with that approach in this application, but tapered bearings are an upgrade and should outlast the OEM bearings.

But how to remove and install the pressed-on lower bearing without the nice factory tools (or a handy machine shop equipped to remove and press the bearings)? Well, the old bearing inner race won't drive off, so I use a Dremel with a cut-off blade and very carefully slice the race with a diagonal cut, stopping just shy of cutting into the shaft itself. Right at that magical point the bearing race gives a little "bing" as it loosens its grip on the shaft — it can then be pried off with a screwdriver blade. In the photo above are (left to right) the new lower seal, the new bearing, the old inner race and the old outer race. I will use the old parts as adaptors to drive the new bearing in place.

(Right) Here I have the parts stacked along with the driver tool — a length of black gas pipe or heavy conduit (with a cap installed to pound on). You can see the diagonal cut I made when removing the old inner bearing race; that cut is not quite all the way through the race. The old and new (inner) races are the same size so the old one makes a perfect driver adaptor to pound the new race onto the shaft.

However you accomplish driving the new bearing onto the shaft, remember that you can never press or pound on the roller cage itself — you have to drive onto the inner portion of the new bearing.

To prepare for driving the bearing onto the shaft, I first put the lower triple tree/shaft assembly into the freezer for several minutes to shrink the metal — frost is visible on the metal in this photo. I then quickly drive the freshly greased bearing into place. I drive the bearing till it just bottoms onto the seal but still turns freely. With the cooled shaft, the bearing slides on pretty smoothly but still requires several hard hits with a hefty hammer.

Job done. Reassemble onto the frame, install the forks, etc., and this project will be back on its own two feet — with a nice, smooth steering action.

16. Refurbishing Paintwork

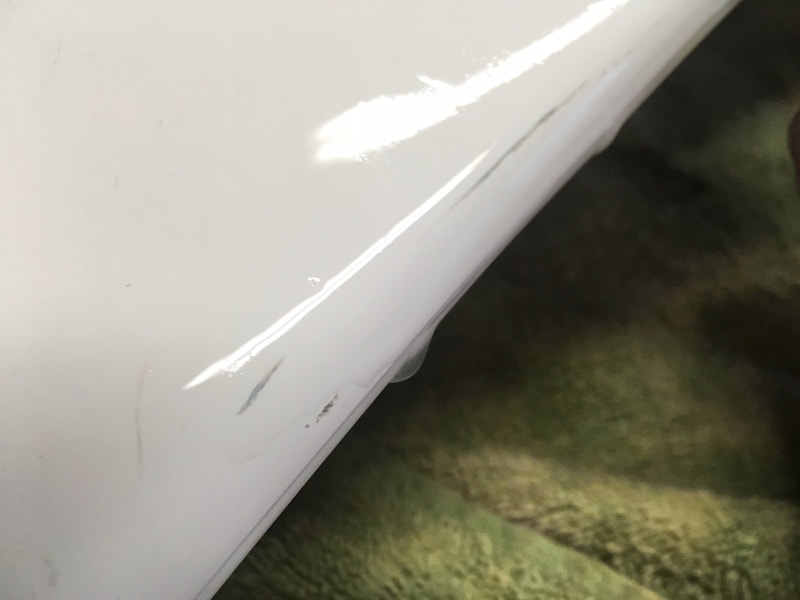

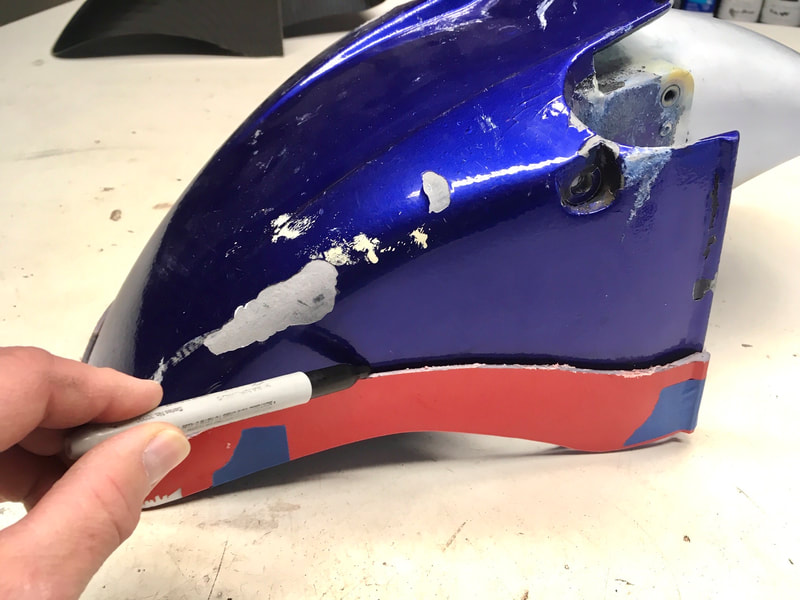

On my projects my goal is always to bring the original paintwork up to the highest level I can. Part of this might involve touching up nicks and scratches, but the real magic can be achieved with a process that I learned as "color sanding." The idea with color sanding is to remove just enough damaged paint to get down through the decades of scuffs, surface scratches and environmental damage — sun, pollution, petrified bugs, whatever.

For the sanding portion of the process I use the finest grit I can get away with, working my way to a final sanding with 5000-grit. 3M provides wet-sanding paper and sponges up to 5000-grit. I begin with the 2000 or 3000 and go rougher only when necessary.

After cleaning the part to be color sanded, I fill a small, clean pail with fresh water with a few drops of dish soap added. With frequent dippings into the water, I gently wet-sand the entire painted area then wipe dry with a clean cloth to check my progress. A deeper scuff may require a stronger grit, remembering that the goal is to achieve the greatest effect but without sanding through the clear coat. This is especially true with pearl paints because the pearl coats are applied on top of the color and sanding away the pearl changes the hue of the finish color.

Practicing on an old part will give a good feel to how much sanding you can get away with before damaging the part with excessive sanding.

Below are a couple of examples of common fairing scuffs that will come right out with a gentle sanding.

(click on images to enlarge)

After cleaning the part to be color sanded, I fill a small, clean pail with fresh water with a few drops of dish soap added. With frequent dippings into the water, I gently wet-sand the entire painted area then wipe dry with a clean cloth to check my progress. A deeper scuff may require a stronger grit, remembering that the goal is to achieve the greatest effect but without sanding through the clear coat. This is especially true with pearl paints because the pearl coats are applied on top of the color and sanding away the pearl changes the hue of the finish color.

Practicing on an old part will give a good feel to how much sanding you can get away with before damaging the part with excessive sanding.

Below are a couple of examples of common fairing scuffs that will come right out with a gentle sanding.

(click on images to enlarge)

This process works just as well on plastic fixtures like tail light, turn signal and headlight lenses. Here I'm using 1000-grit paper on a tail light lens, which I will follow up with 1500, 3000 and 5000. Yeah, it's a lot of sanding.

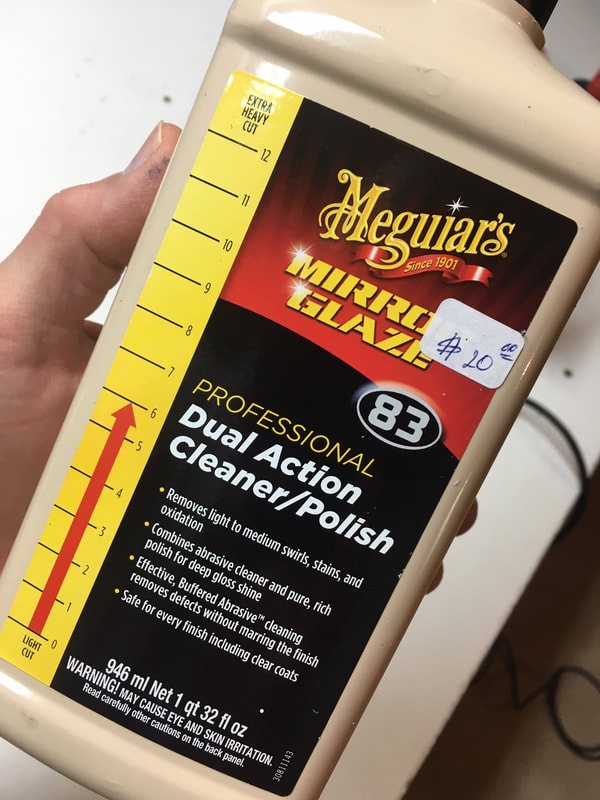

(Below) For the buffing portion of this process I use my Griot's Garage small orbital polisher with 4-inch buffing pads. I have a selection of compounds but my go-to is Meguiar's Ultimate Compound. If I think a stronger grip is called for, I'll buff first with Meguiar's Mirror Glaze #83 or similar. The lower right photo shows a sanded vs. buffed portion of the tank. I finish up with a quality wax, hand applied.

(Below) Some of the finished product.

17. Carburetor Removal

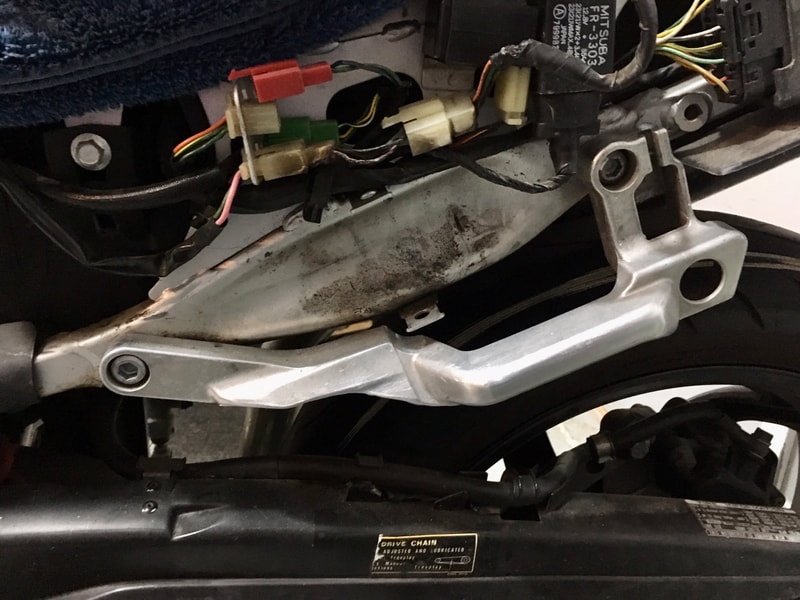

This tutorial will demonstrate carburetor removal on a 1986-87 VFR but 1st-4th generation bikes are very similar — consult your service manual.

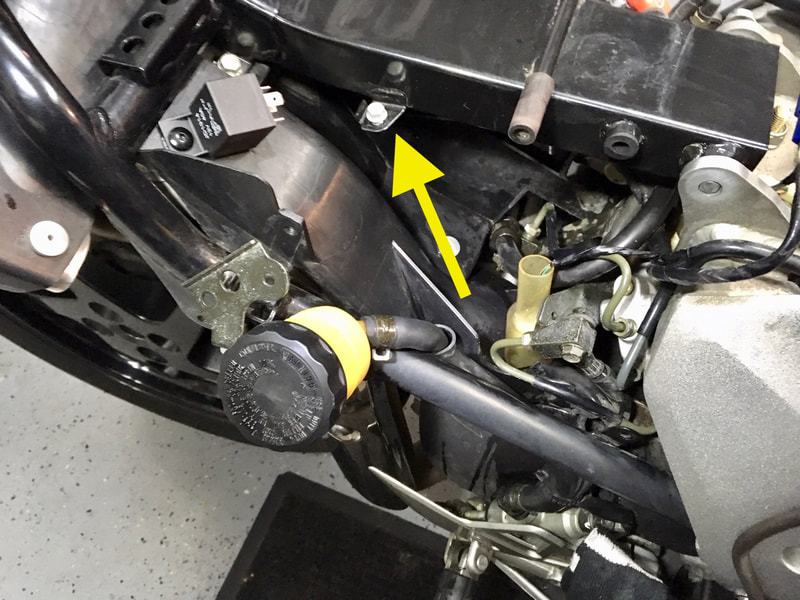

(Below) I start with radiator removal. I do this when I know that I'll be doing a valve adjustment check and having the radiator completely out of the way makes the process much easier. If you're only servicing the carbs this isn't a necessary step but it's not difficult, gives more working room and allows easier cleaning of the area, if you like. Drain the coolant via the lower radiator hose, remove the two hoses, unbolt the one upper and two lower mounting bolts, unplug the fan electrical connector (right side of bike, under headlight fairing), slide the radiator to the right to unhook from its hanger stud, then lower and remove the radiator from the left side.

NOTE: The photo on the right shows the emissions evaporative canister and other hardware, indicating a California-spec bike. I will show how to remove this system.

(click on any of the small images to enlarge)

(Below) I start with radiator removal. I do this when I know that I'll be doing a valve adjustment check and having the radiator completely out of the way makes the process much easier. If you're only servicing the carbs this isn't a necessary step but it's not difficult, gives more working room and allows easier cleaning of the area, if you like. Drain the coolant via the lower radiator hose, remove the two hoses, unbolt the one upper and two lower mounting bolts, unplug the fan electrical connector (right side of bike, under headlight fairing), slide the radiator to the right to unhook from its hanger stud, then lower and remove the radiator from the left side.

NOTE: The photo on the right shows the emissions evaporative canister and other hardware, indicating a California-spec bike. I will show how to remove this system.

(click on any of the small images to enlarge)

(Below) To begin the carb removal, remove the air cleaner and housing. Be prepared for anything when the cover comes off — in this case only a few mouse meal remnants were found, and no telltale mouse pee smell. That corrosive liquid will work its way downward into the carbs and wreak all kinds of havoc. These carbs look very clean. That's a UNI brand foam/oil filter and its life is over.

(Below) Next, I unscrew the four upper carb boot ("insulator") clamps. The lower clamps can remain tightened. Then loosen, but don't remove, the choke ("enricher") cable clamp. Leave the screw in place to prevent dropping the assembly now or during reassembly. Unhook the choke cable.

(Below) I then remove the two throttle cable bracket screws (left photo) which allow the cables to be slackened and easily removed — there's no need to touch the adjustment nuts. My first indication that these carbs have been dealt with before is that the lower bracket screw is not OEM.

(Below) Now the emissions stuff needs to be dealt with. I just cut the five hose connections in question, but they can also be removed if you wish to re-use the hardware. In this case, one of the vacuum hoses was cracked and leaking at carb #4, which highlights the issue with this old emissions hardware — lots of opportunities for difficult-to-find leaks. In any case, here's the connections.

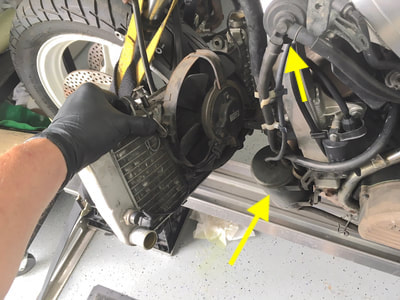

(Below) Let's get the carbs off. With everything loose, the rack is ready to lift off, but it will be stuck pretty tightly, so I gently lever the rear half free and then lift straight up to remove. I use a bent-tip lever with the yellow plastic scraper protecting the valve cover, and lever straight up under the rearmost carbs (#1 & #3), gently pushing upward at the lower point of the diaphragm cap (left photo). On the later models, try levering off to the side (right photo, courtesy of Juan O.). If they seem immovable, check that the boot screws are very loose and keep gently working them upward. Please resist the temptation to resort to a hammer. Once the rear is free, lift off the carb set.

(Below) With the carbs on the bench, drain the float bowls into a container using the drain screws. Have a peek with a flashlight into the engine's intake tracts for skeletal remains or any other debris, then stuff some clean paper towel into the tracts. If you're going to clean the engine area, cover the intake holes with squares of cut-up plastic bag and zip-tie in place to keep water out. On the 2d-gen, the plastic covers from Edge brand shave cream cans fit perfectly.

(Below) Here's what you should see in the intake tract; nice and clean with not too much carbon build-up on the valve stems. You may also see some blue scribbling on the engine block. Those are notes from the assembly line. Tip: Replace that little radiator hose before reinstalling the carbs. See tutorial #13, Small Coolant Hose Generic Replacement.

(Below) If you're planning a valve clearance check, you'll want to remove the air baffling above the front cylinders. This plastic cover is held in place by plastic "plugs" firmly stuffed into frame holes on either side. I use two flat-blade screwdrivers to pry the plug upward completely out of its hole. Shown here is the left side; the right is a tighter fit because of the wiring harness passing above it — just wrestle the harness out of the way. Lift the baffle on the left side, then out. Tip: Install in reverse: lower the right side into place first. That deteriorating brown foam stuff is sound deadening — as it disintegrates it will be sucked into the air cleaner housing. Feel free to scrape and scrub it off.

If you'll be removing the emissions hardware, follow each hose to its end point and unbolt the hardware. I'll toss it all and simply vent the line exiting at the rear of the carbs into the air; that's how it's done on the 49-state bikes. There's also five small vent tubes at the carbs which will need to be plugged. I'll cover that in the next tutorial.

Here's a look at the discarded hardware.

Job done!

Here's a look at the discarded hardware.

Job done!

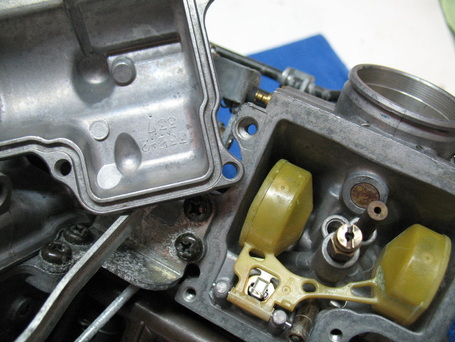

18. Carburetor Disassembly, Cleaning, Reassembly

In this tutorial I'll show a basic cleaning of the carburetor set on a 1986 California-spec bike. All the generations of VFR carbs are similar, just a bit more complex with each subsequent generation — consult your service manual.

I begin with the carb set on a clean workspace with the fuel drained. For this basic cleaning the carb rack can be kept assembled to the plenum, and linkages left in place.

TIP: If you've got the carb set on the bench like this, seriously consider the benefit of replacing the fuel tube o-rings; see tutorial #1, which will also allow for a more thorough cleaning.

(Below) I first completely disassemble the components, separating them with respect to their individual carb; not really necessary, but probably not a bad idea. Inspect each part for condition as you remove it, paying particular attention to the slide diaphragms. I scrub the bare carb set in the sink with a water-based degreaser and hot water rinse, and give the small parts a dunk in an ultrasonic cleaner (if available). All the passageways are given a blast with compressed air and verified clear — I do this by attaching a short piece of hose to each orifice and blowing by mouth, listening for the escaping air. As a matter of course I replace the float bowl gaskets and air screw o-rings along with the fuel tube o-rings and fuel lines (see appropriate tutorials).

I begin with the carb set on a clean workspace with the fuel drained. For this basic cleaning the carb rack can be kept assembled to the plenum, and linkages left in place.

TIP: If you've got the carb set on the bench like this, seriously consider the benefit of replacing the fuel tube o-rings; see tutorial #1, which will also allow for a more thorough cleaning.

(Below) I first completely disassemble the components, separating them with respect to their individual carb; not really necessary, but probably not a bad idea. Inspect each part for condition as you remove it, paying particular attention to the slide diaphragms. I scrub the bare carb set in the sink with a water-based degreaser and hot water rinse, and give the small parts a dunk in an ultrasonic cleaner (if available). All the passageways are given a blast with compressed air and verified clear — I do this by attaching a short piece of hose to each orifice and blowing by mouth, listening for the escaping air. As a matter of course I replace the float bowl gaskets and air screw o-rings along with the fuel tube o-rings and fuel lines (see appropriate tutorials).

(Below) This carb set was pretty grungy on the outside, but surprisingly clean inside. Unscrew the two brass jets — using a proper-fitting screwdriver blade push firmly downward and give a sharp twist to break the jets loose; the soft brass will break if the wrong sized blade is attempted or if forced. The smaller is the low-speed jet and is susceptible to clogging from old fuel deposits. Verify it's clear or just replace — I always replace the #38 ('86-87) with a #40 (later years use #40 from the factory). Pull the float pins and lift the float and needle, noting how the needle hangs loosely on the float tang. That tang is bent slightly up or down to adjust the float during reassembly ('86-93, '94+ are non-adjustable).

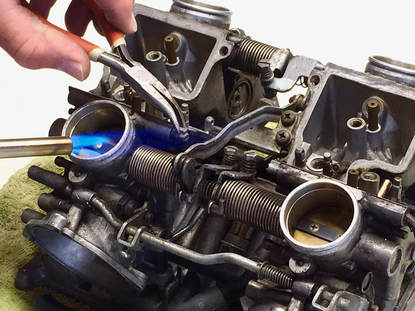

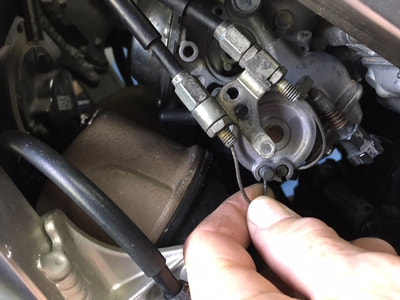

In order to remove the pilot screw adjusters, the factory caps need to be removed. This is made easier by applying heat from a small torch while gently pulling on the cap till it pops off. Be cautious with the heat, the metal used on these carbs has a low melting point. The caps are an emissions thing (to prevent owner tampering) and don't need to be reinstalled unless desired. The screwdriver groove will have some grunge in it so clear that out with a small blade.

In order to remove the pilot screw adjusters, the factory caps need to be removed. This is made easier by applying heat from a small torch while gently pulling on the cap till it pops off. Be cautious with the heat, the metal used on these carbs has a low melting point. The caps are an emissions thing (to prevent owner tampering) and don't need to be reinstalled unless desired. The screwdriver groove will have some grunge in it so clear that out with a small blade.

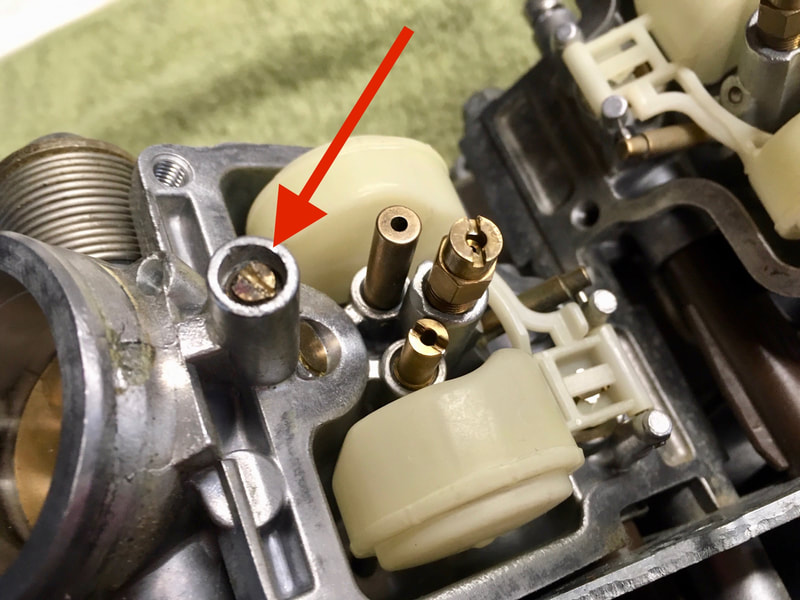

(Below) Turn out the screw, being very careful to avoid losing the spring, washer and o-ring inside. These little parts are NLA from Honda, though I have sourced replacements for the o-ring and metal washer (see Products page) and aftermarket rebuild kits should include them. I use a small nail or stiff wire with a bent tip to dig for the washer and o-ring if they're left stuck inside the hole. Inspect the needle for a bent or broken tip; it should look like the one pictured. NOTE: I have seen a video where the presenter indicates that these o-rings don't belong here — that's incorrect information.

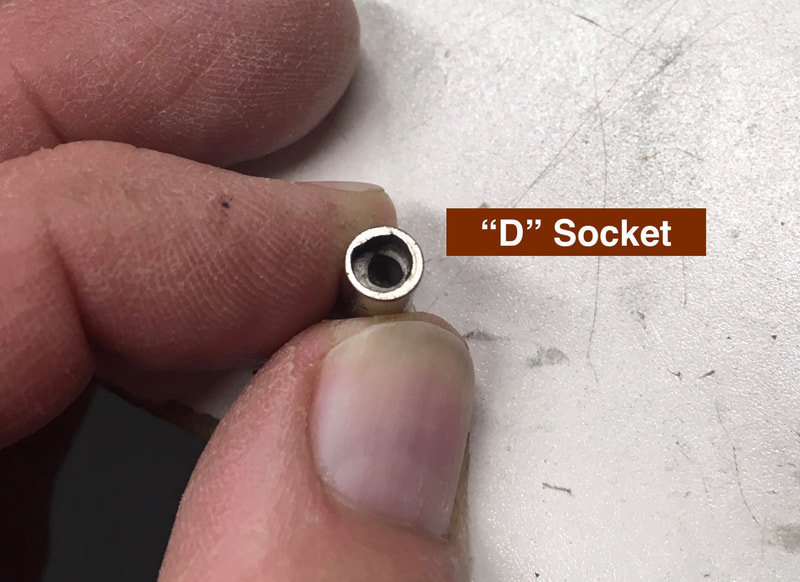

(Below) Here's the pilot screw location on the fourth-gen (1994-97). It requires a special "D" shaped socket. Once removed, I cut a groove into the screw head to allow the use of a straight-blade screwdriver in the future, but not necessary.

(click on a image to enlarge)

(click on a image to enlarge)

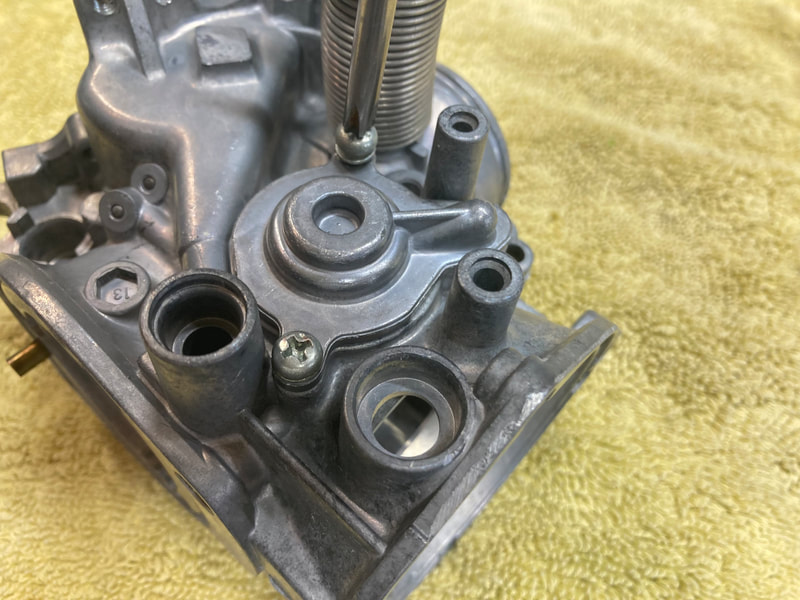

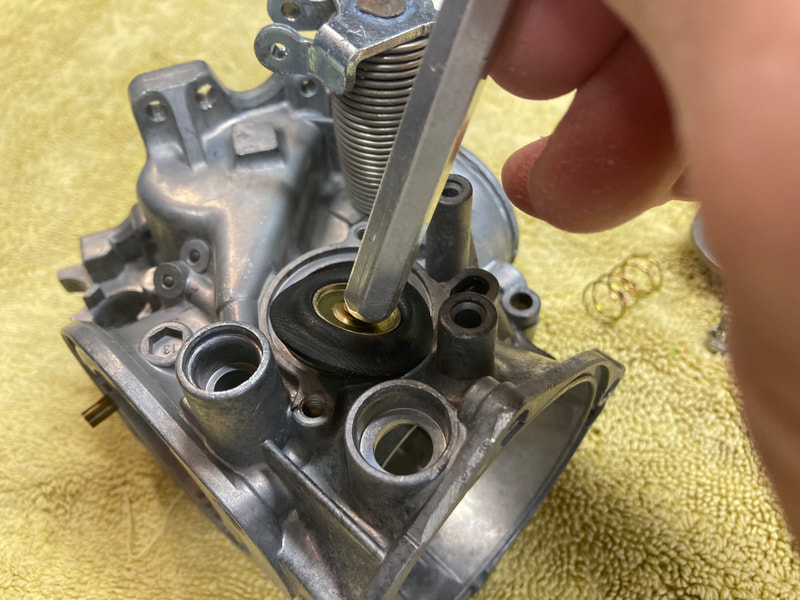

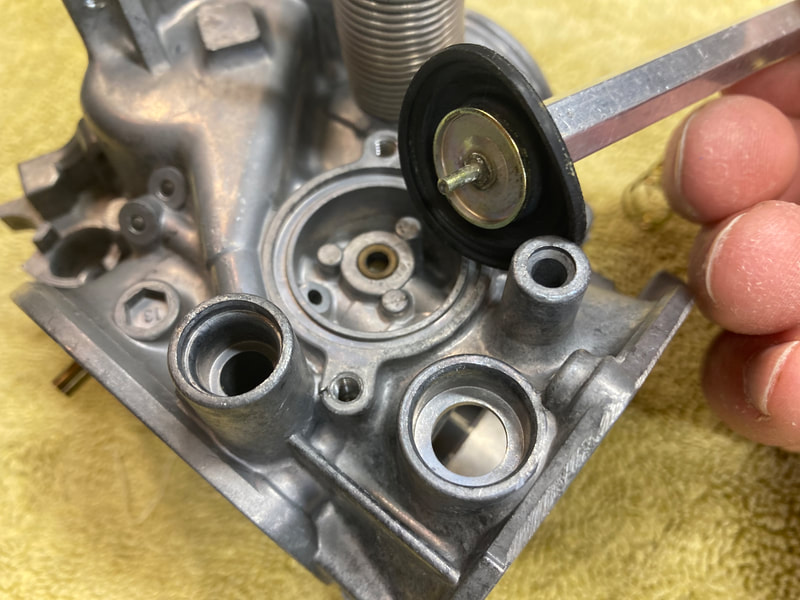

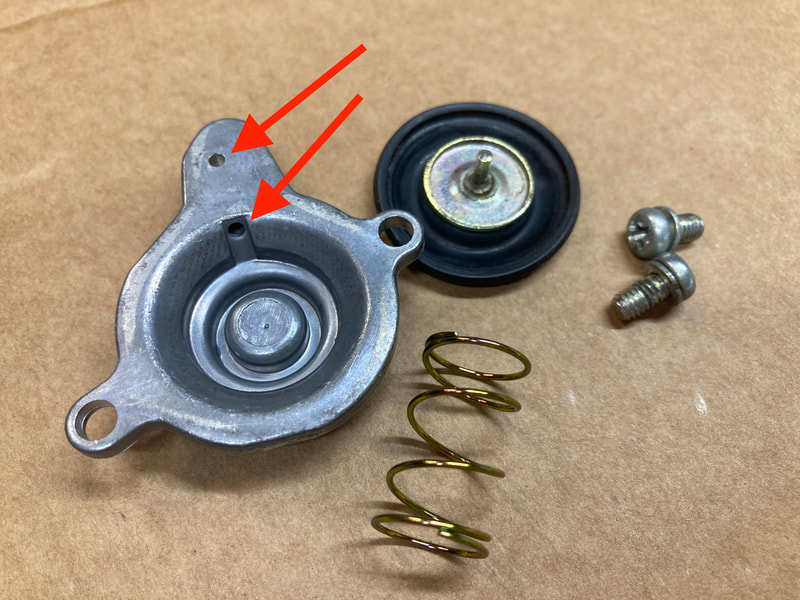

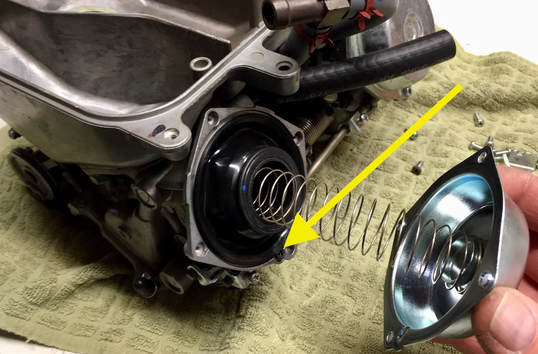

(Below) An additional component found on the 3d- and 4th-gen (1990-97) carbs is the Air Cut Valve assembly. The valve's function, as I understand it, is to prevent popping on deceleration (closed throttle). The valve is generally in reusable condition and servicing is a simple procedure.

We begin by removing the two cover screws. Inside we find a strong spring and the metal/rubber diaphragm (below). The diaphragm is usually slightly stuck in place, and rather than risk damaging the rubber, I use a small magnet to gently pull it free. Note the oval o-ring (arrow). These parts are no longer available from Honda but aftermarket kits are available. However, your parts are reusable if undamaged, so handle with care. Gently remove this o-ring for safekeeping during cleaning. I wash the parts and blow the air passage shown (two red arrows) clear with compressed air, along with the two passages in the carb body. Reassembly is simple, but that's a strong spring to hold pressure on while locating the screws.

We begin by removing the two cover screws. Inside we find a strong spring and the metal/rubber diaphragm (below). The diaphragm is usually slightly stuck in place, and rather than risk damaging the rubber, I use a small magnet to gently pull it free. Note the oval o-ring (arrow). These parts are no longer available from Honda but aftermarket kits are available. However, your parts are reusable if undamaged, so handle with care. Gently remove this o-ring for safekeeping during cleaning. I wash the parts and blow the air passage shown (two red arrows) clear with compressed air, along with the two passages in the carb body. Reassembly is simple, but that's a strong spring to hold pressure on while locating the screws.

(Right) This main jet needle is stock OEM, which tells me that no jet kit was installed in this carb set. The needle assembly can be left in place, or the manual shows how to remove it using an 8mm socket in the event you want to replace it (bent needle or jet kit install) or add an additional shim (to lift the needle further). Inspect the diaphragm for holes by holding it up to a light source and gently spreading the rubber.

(Right) Here's a shot of an aftermarket jet kit needle, in this case a DynoJet needle on a 4th-gen "semi-flatside" slide.

I like to clean up the slide bore with some fine steel or aluminum wool, especially if it looks like this. Here's the result of 20-year old varnished gas. These slides were very difficult to extract.

Note that the float diaphragm has a locating tab, with a corresponding depression in the cap (1986-93).

TIP: With your middle finger, hold the slide up in its bore while assembling the spring and cap with your other hand. This helps to keep the diaphragm seated during assembly.

Assemble the pilot screw (spring, then washer, then o-ring), and install by gently seating it, and then back off to specification, or I use 2 3/8 turns for OEM, and 2 3/4 turns with a jet kit ('86-87).

NOTE: These pilot screws meter fuel (not air), so turning out increases fuel, thereby enriching the mixture.

(Right) Check the float settings — the manual uses a special tool, but a ruler can be used (don't tilt the ruler like this!). I shoot for a 9mm height ('86-93), the '94-97 floats don't adjust.

Apply a bit of light oil to the pivot points of the throttle and choke linkages, and butterfly plates.

Be sure there's no left-over parts, and recheck all your screws; no need to over-tighten.

(Below) If applicable, the five California-spec vent tubes will need to be capped. I source 3/16" silicone caps from Amazon, secured using the original OEM spring clamps. For a more positive and permanent fix, I install sheet metal screws slathered with JBWeld or similar; one #6 for the small tube and four #8 for the larger ('86-87 shown). Your carbs are ready to be leak tested (tutorial #20), then installed.

(click on an image to enlarge)

(click on an image to enlarge)

(Right) An additional aspect of California-spec bikes is the method of fuel tank venting. Instead of venting through the filler cap the CA bikes vent through a tube in the front underside of the fuel tank. DON'T PLUG THIS VENT. Check that the vent isn't clogged by back-blowing through it, then run an open hose downward through the front area of the frame and terminate somewhere safe and out of sight.

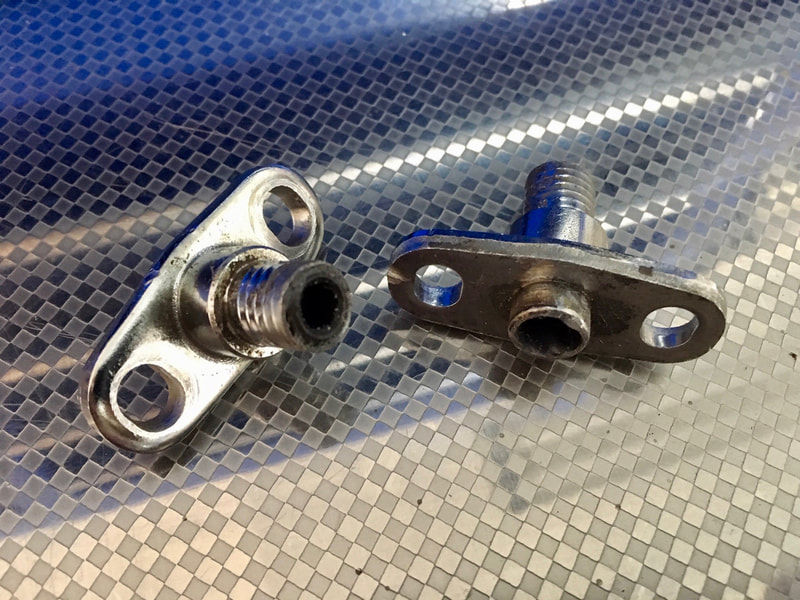

19. Preparing For Carb Sync

Before installing the carburetor set, and in anticipation of syncing the carbs, I'll want to attach the tool's adaptors and hoses. This is much easier with the carbs off the engine.

I use a Morgan Carbtune. After struggling with liquid manometer devices I discovered the Carbtune and it's found a permanent home in my toolbox.

I use a Morgan Carbtune. After struggling with liquid manometer devices I discovered the Carbtune and it's found a permanent home in my toolbox.

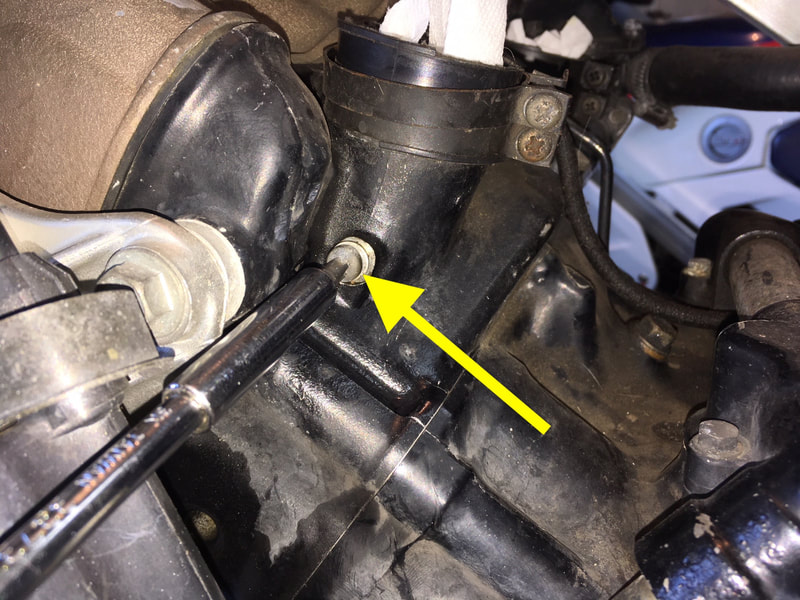

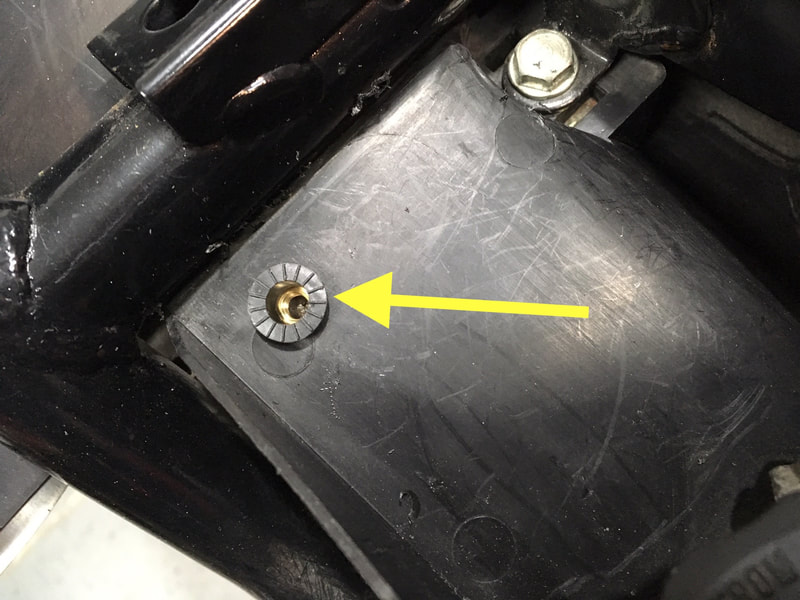

(Below) The adaptors are screwed into the intake manifold vacuum ports. Remove the screw and washer in each manifold. On California-spec models and 1990+ models, two or more of the ports will have hose adaptors in place for the emissions hardware. Remove and later replace with solid screws if you're removing the emissions hardware, as I am on this California-spec 1986 VFR750.

(Below) The adaptors are lightly screwed in place (Morgan now uses brass adaptors); no need to compress the rubber o-ring beyond what's needed to make a seal. I then connect the hoses to the adaptors, which I've labeled #1 through #4, and plug the ends with golf tees. Later, when I'm ready to sync, I'll remove the tees and connect to the gauge.

Ready for carb installation.

Ready for carb installation.

20. Carburetor Installation

As your shop manual likes to say, "installation is the reverse of disassembly." Which is true, but here's a few tips I've learned over the years.

NOTE: I will be syncing these carbs once the engine is running, so before proceeding with this install, I've connected the sync tool's vacuum hose adaptors and hoses — see the previous maintenance tutorial, "Preparing For Carb Sync" for details.

TIP: Check your carbs for leaks before installing: see my technique at the bottom of this post.

If your carb insulators (manifold boots) are hardened with age, simplify your life by installing fresh boots, the '86-87 boots are still available from Honda, later years from the aftermarket. First remove the lower clamps and, with a large pliers, give the old boot a firm tug to remove. Clean up the area and push the new boot into place, noting that the groove adjacent to the word "Carb" is oriented to 12-o'clock (below). Install all eight boot clamps and thoroughly tighten the lowers. TIP: I orientate '86-87 clamps to the left which I find makes access easier, using a long shaft screwdriver.

NOTE: I will be syncing these carbs once the engine is running, so before proceeding with this install, I've connected the sync tool's vacuum hose adaptors and hoses — see the previous maintenance tutorial, "Preparing For Carb Sync" for details.

TIP: Check your carbs for leaks before installing: see my technique at the bottom of this post.

If your carb insulators (manifold boots) are hardened with age, simplify your life by installing fresh boots, the '86-87 boots are still available from Honda, later years from the aftermarket. First remove the lower clamps and, with a large pliers, give the old boot a firm tug to remove. Clean up the area and push the new boot into place, noting that the groove adjacent to the word "Carb" is oriented to 12-o'clock (below). Install all eight boot clamps and thoroughly tighten the lowers. TIP: I orientate '86-87 clamps to the left which I find makes access easier, using a long shaft screwdriver.

(Below) I wipe a film of grease or something similar on the lip of the boots to help the carbs slip into place. The upper clamps should be loosely in place. Place the carb set square to the front boots and push firmly down till seated in the front boots, verifying with a flashlight that they're seated. To get the rears in place, while standing on the left side of the bike, I maintain downward pressure with my left hand while running the blade of a flat screwdriver along the inside of both rear carb boots with my right hand. If your boots are fresh and supple they will "pop" into place after repeating the screwdriver trick two or three times. Tip: if you're in a cold environment, adding heat to the boots with a heat gun will help soften the boots. Resist the temptation to resort to hammering on the carb set to seat the rear carbs — you'll likely break a chunk off the metal plenum.

(Below) Tighten the upper boot clamps making sure that the clamp is square in its groove all the way around. Use a flashlight to verify this as you're tightening the clamp. The 1990+ clamps have an upgraded design to hold them in their grooves, but the earlier models don't. Next, Install the throttle cable ferules, then the cable bracket's two screws. Install the choke cable ferule, adjust to get slight tension on the cable, then tighten into its clamp. Tip: A long screwdriver is invaluable to reach the right side carbs ('86-87), and a JIS screwdriver is always recommended.

Finally, install the complete air filter housing along with the type of air filter that you plan to use. (Right) In this case I'll be using a K&N filter so I'll remember to remove the rubber gaskets in both the top and bottom air filter housings. The K&N won't fit correctly with those gaskets in place. I'll keep them in case a future owner wants to go back to OEM.

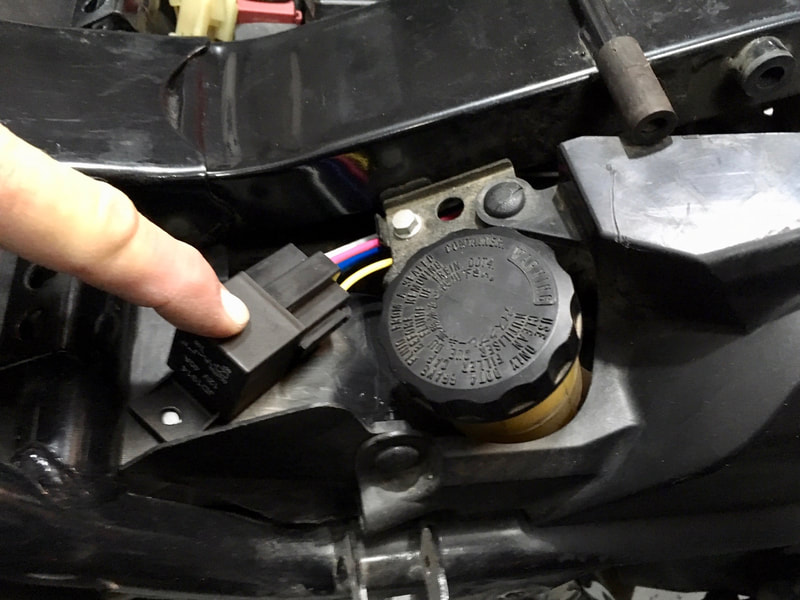

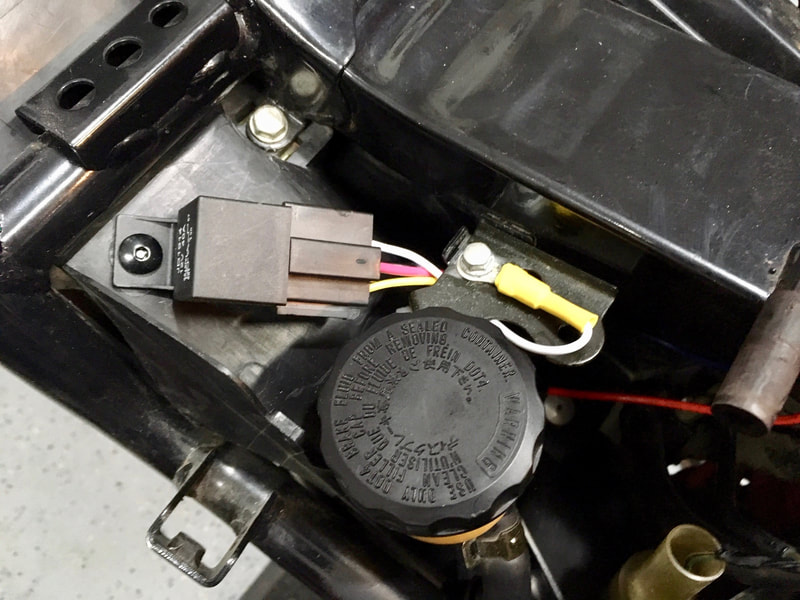

(Right) At this point I'll connect the fuel bottle direct to the carb intake line in preparation for engine start. If you do this, disconnect the fuel pump power supply at its connector just above the pump. The pump relay can remain connected.

You can also use the fuel bottle or the bike's fuel tank with all its plumbing, pump, relay, etc. hooked up.

You can also use the fuel bottle or the bike's fuel tank with all its plumbing, pump, relay, etc. hooked up.

With the radiator reinstalled (and filled), double check all your connections, connect the battery, and we're ready to hit the magic button!

Allow the engine to warm for about ten minutes, shut down, and connect the sync hoses to the tool to sync the carbs; see tutorial #21, "Carburetor Synchronizing."

Leak Check

Here's a tip I learned the hard way. You'll want to check your carb work for leaks, and having the carbs completely mounted is not the best time to do that — if there's a leak it'll be dripping all over your engine or, worse, overflowing through the vents directly into the intake manifolds and down into the engine. Save yourself all that potential grief by checking the carbs on the bench.

I simply place the carb set into a large tub (a cat litter tub is perfect), connect the fuel bottle, open its spigot, and let them sit for at least a few hours, overnight is best. Any leaks are contained, and because the carbs are off the bike, finding and fixing a leak is less painful.

Here's a tip I learned the hard way. You'll want to check your carb work for leaks, and having the carbs completely mounted is not the best time to do that — if there's a leak it'll be dripping all over your engine or, worse, overflowing through the vents directly into the intake manifolds and down into the engine. Save yourself all that potential grief by checking the carbs on the bench.

I simply place the carb set into a large tub (a cat litter tub is perfect), connect the fuel bottle, open its spigot, and let them sit for at least a few hours, overnight is best. Any leaks are contained, and because the carbs are off the bike, finding and fixing a leak is less painful.

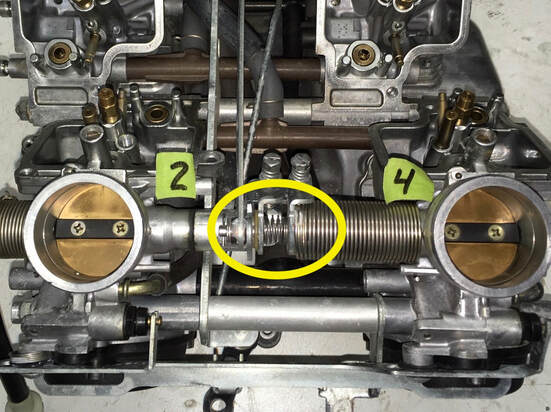

21. Carburetor Synchronizing

For our purposes carb syncing is the process of setting the individual carb's butterfly valves to open at the same time. The effect is to provide equal amounts of air (and thus fuel) giving us the most power and smoothest operation. This is a crucial step in tuning any multi-cylinder engine, but especially highly tuned, high-performance ones like the V4 Interceptor.

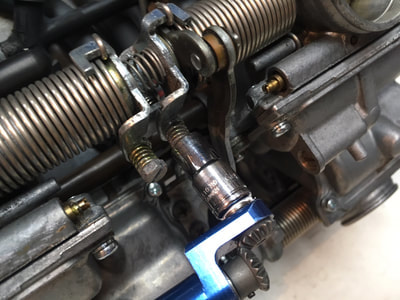

It's a simple concept with the only difficult part being actually getting to the set screws. That's where the Motion Pro 90-degree Hex Driver comes into play.

It's a simple concept with the only difficult part being actually getting to the set screws. That's where the Motion Pro 90-degree Hex Driver comes into play.