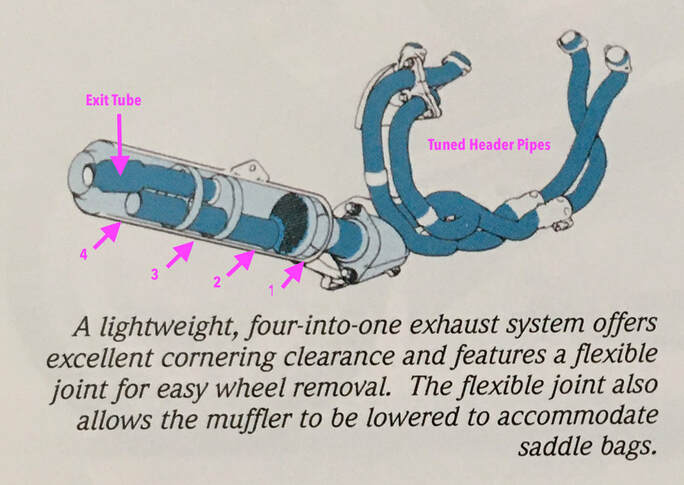

Years ago I decided to dissect a second-gen muffler just to see what's going on inside and maybe modify a stock muffler for better sound. I discovered that Honda had accomplished their goals in a typically engineering-oriented approach, without the use of sound deadening material (which wears out) or acres of perforated baffling, which adds weight and rusts out. The image below is from a Canadian dealer informational brochure showing a diagram of the OEM muffler for the 3d-gen (the pink notations are mine).

There's four sealed chambers, the airflow progressing rearward through the blue-colored tubes all the way to chamber #4, then forced to make a 180° turn, forward to chamber #2 through holes in the chamber walls, then another 180° turn rearward through the exit tube and out the rear. The sound is mitigated by the forced turns and chambers #2 & 4 absorbing the sound waves — at least that's how my non-engineering mind sees it. Air doesn't like making turns, particularly 180° turns, so back pressure is created, which is engineered to work in conjunction with the cool tuned header pipes. Ever wonder why those front pipes cross over one another? That's part of the complicated tuning of pressure pulses.

All that internal steel piping adds weight and takes up real estate, which is why the aftermarket has a much easier job in creating lighter, louder, more compact mufflers. Do they work better? Typically not, but they often sound better, or at least louder, at the expense of hearing loss and irate public opinion. The only way to achieve actual performance benefit is to tune an entire system, including intake and carburetion, to work together, but that's a doctoral thesis in itself. The Hindle system is an example.

A simple tin canister? No so much.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed