In his own words, "“Where it will end, no one knows. But you can be sure I’m going to enjoy every minute I have left, with a smile on my face, and my family nearby. Can’t ask for more than that.”

|

Malcolm Smith 1941-2024 This past week our sport lost a moto legend. Malcolm Smith was an amazingly successful rider, beloved and respected by the motorcycling world, considered by anyone who met him, even briefly, to be everyman's motorcyclist — genuine, kind, fun, enthusiastic, and North America's perfect motorcycling ambassador to the world. Probably best known for his on-screen contributions to the film, "On Any Sunday," he earned his fame by being one of the best off-road competitors around the world. Motorcycling was his life, and we're all the better because of that.

In his own words, "“Where it will end, no one knows. But you can be sure I’m going to enjoy every minute I have left, with a smile on my face, and my family nearby. Can’t ask for more than that.”

0 Comments

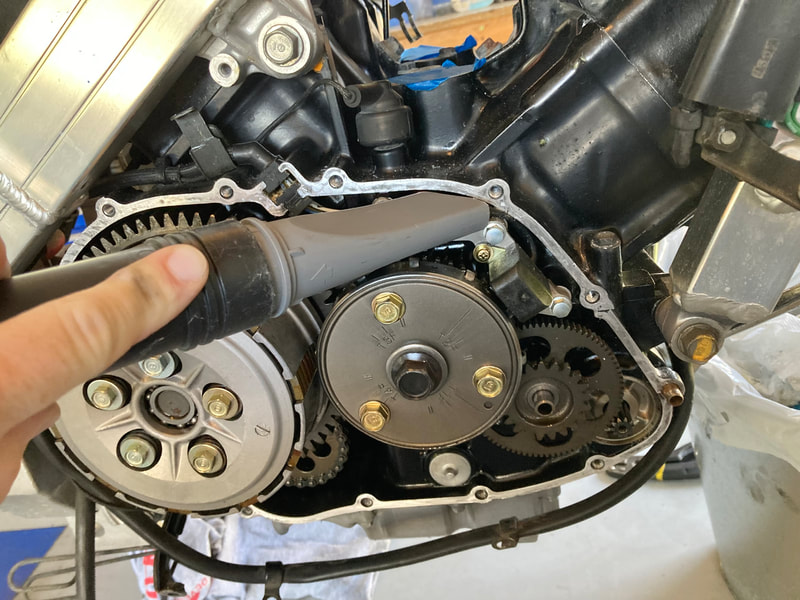

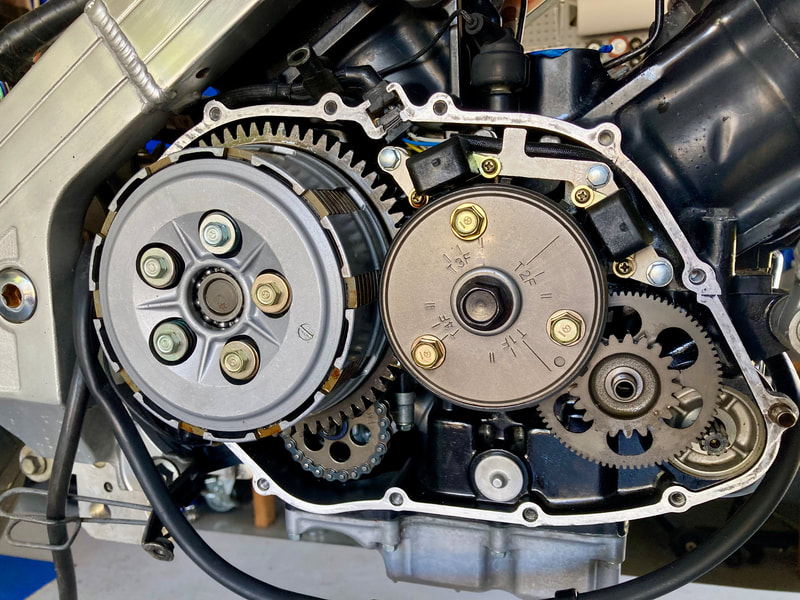

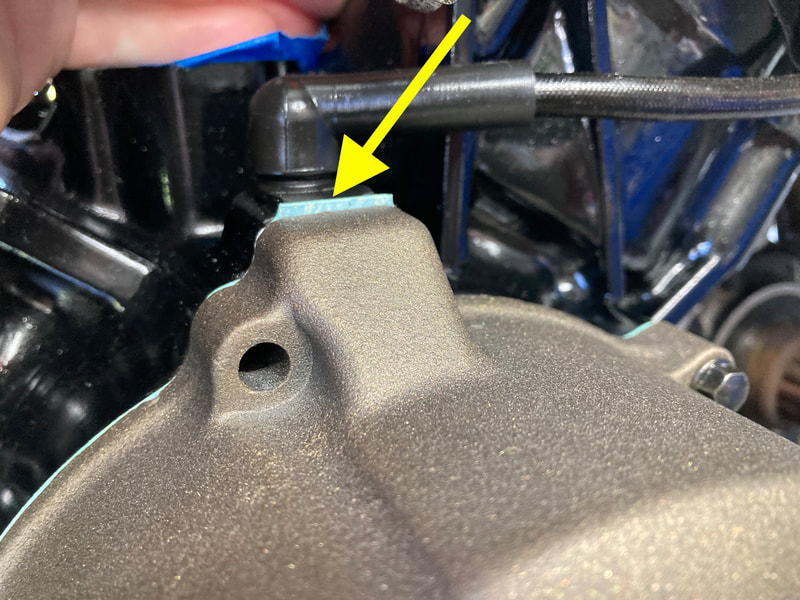

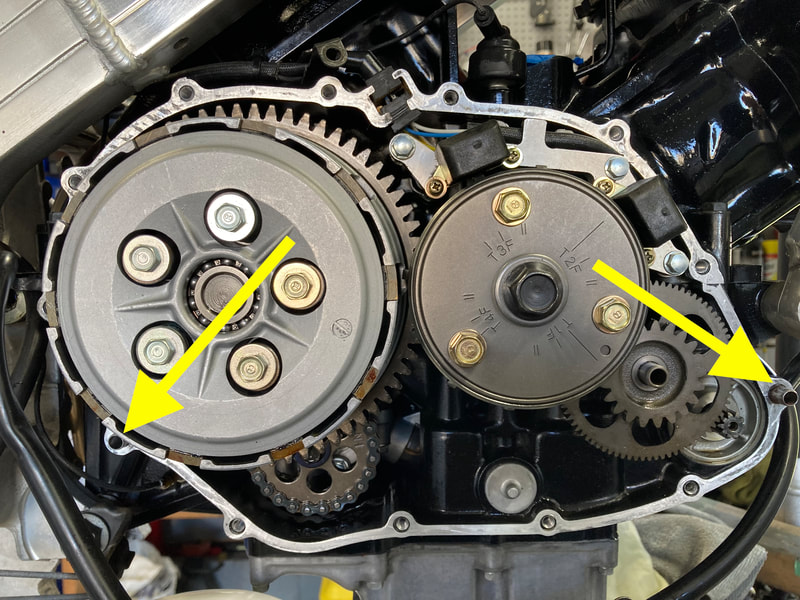

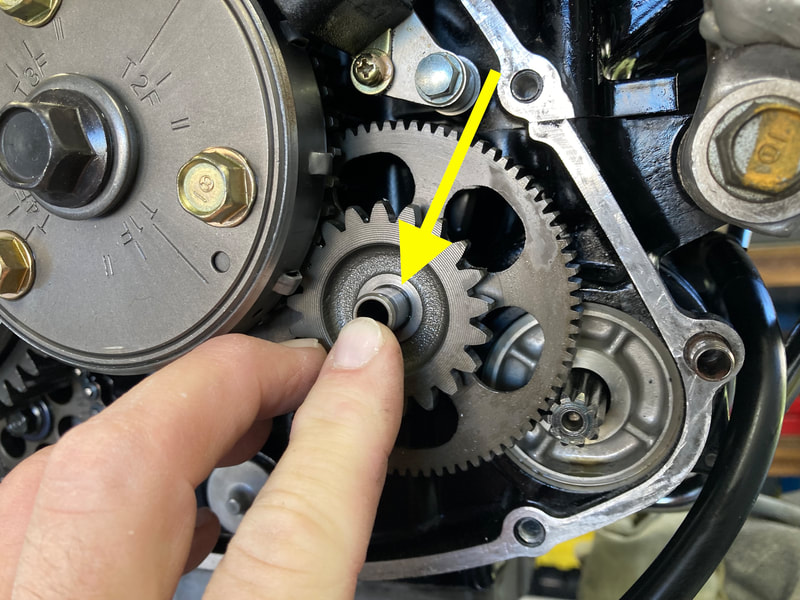

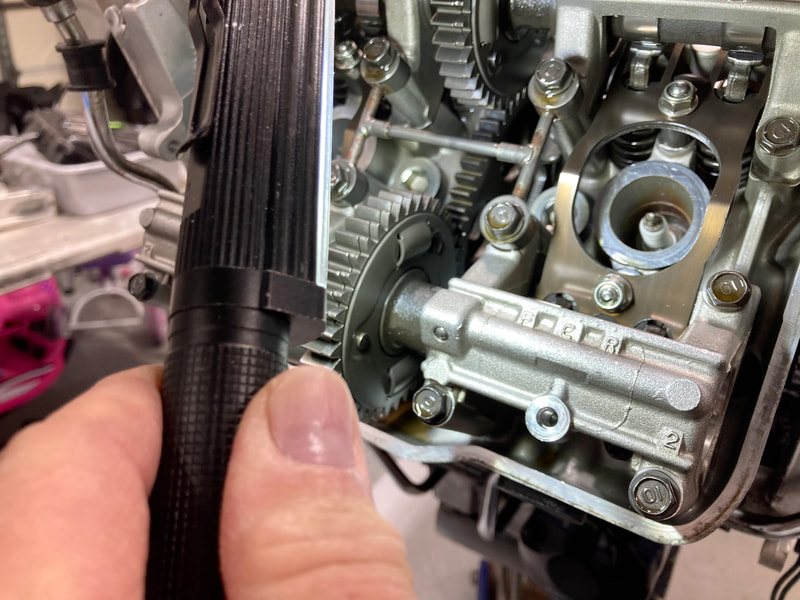

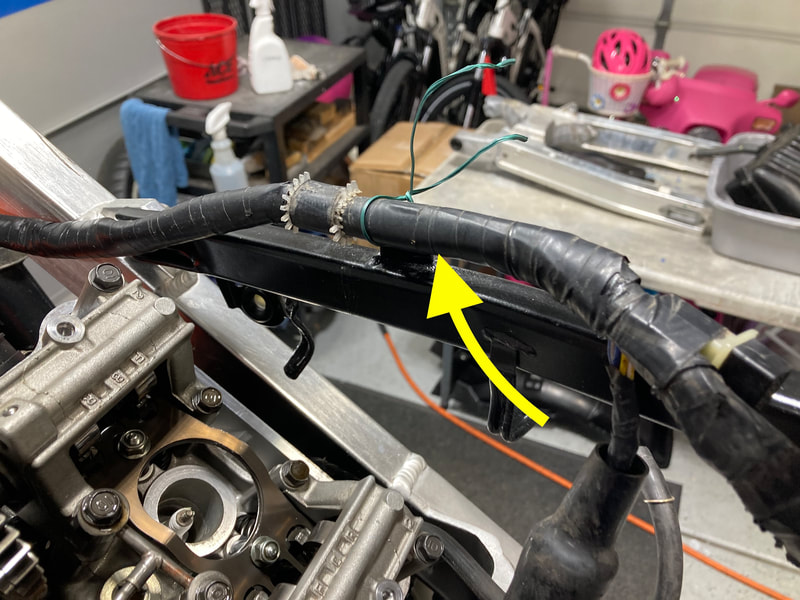

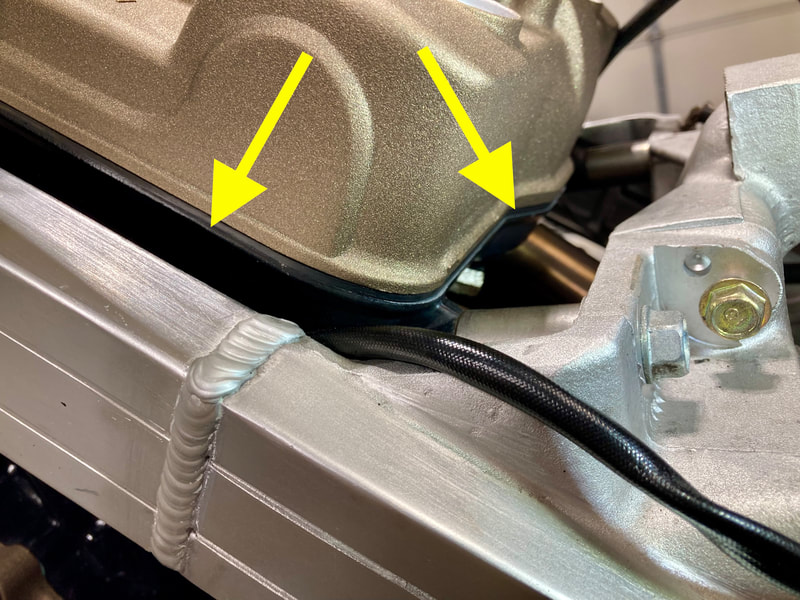

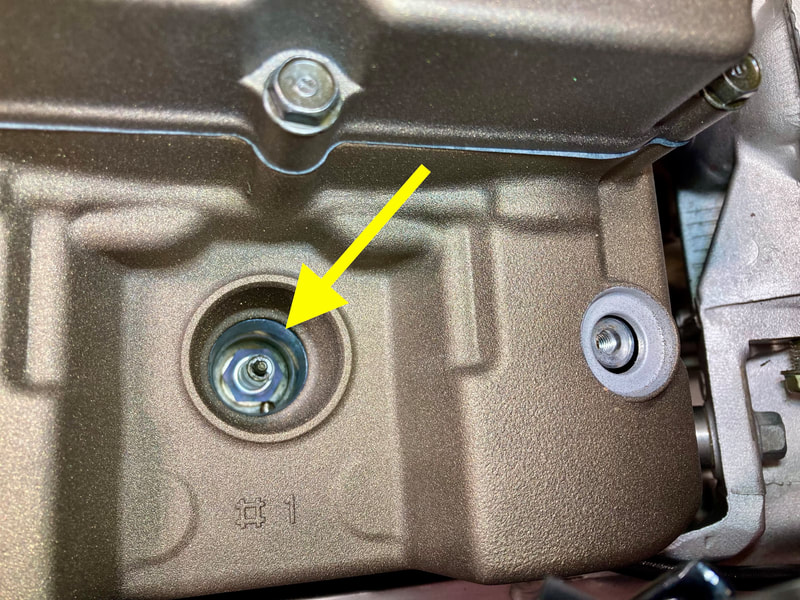

"Installation is the reverse of removal" — an oversimplification common to service manuals since the dawn of the industrial revolution. While completely accurate in an objective sense, there's often a few beneficial tips to help keep the gears meshing and that black gold inside the machine where it does the most good. This post shows my work on Project 41, a Gen-2 VFR, but it generally applies to all years. (Below) The very first step is to prepare the gasket surfaces to ensure a leak-free mating. The covers' were done before powdercoating but the engine surfaces are more of a challenge. There's a lot of interior crevices where bits of dirt and old gasket can disappear, and we don't want that stuff circulating around our engine internals. I position paper towel around the perimeter and carefully scrape the surfaces with whatever I can make work. My favorite gasket scraper is the excellent Bahco pull tool shown here, but I also use a traditional scraper and small bits of crocus/emery cloth (sandpaper for metal). The surface needn't be virgin aluminum, but it does need to be smooth. Be careful to avoid gouging the soft aluminum surface, but if you do, fill the gouge with gasket cement during installation. Bahco #625 gasket scraper is available on eBay: $21 Finally, I vacuum the area and go after any leftover debris with a thin cloth on a screwdriver tip wetted with a bit of grease — the debris will stick to the grease. When everything is clean, I proceed to the gasket and cover. (Below) But first I complete any cleaning around the area, including detailing the fasteners (previous post), blowing out the threaded holes and shining up the nearby wiring and hoses, like the starter cable shown here. Check for chafing on the pulse generator wire harness where it touches the sharp edge of the gasket surface (yellow arrow). (Below) I begin with the alternator cover using a dry gasket and tightening the bolts sequentially in a crosswise pattern. Here I'm speeding up the process with a cordless drill with a socket adapter and the drill's clutch set to a very low torque. I do the final tightening by hand — note the radiator hose support bracket. I've never found a torque setting but not much is required, maybe 8-10 Lb/Ft? "Tight but not too tight," as my Dad would say. I didn't like the look of the excess gasket peeking out at the top, so I trimmed it with a razor. (Below) Moving to the clutch cover, note the location of the two dowels, which are also the location of the two longer bolts — all the clutch and alternator bolts are the same length except for these two. (Below) Before installation, make certain that the bushing holding the primary drive gear assembly is firmly seated (arrow). This is the same bushing that you hoped would not pull free when you removed the cover from the engine — if it did, you'll have a 3-handed puzzle getting those gears meshing together correctly. That bushing locates in the cover's recess shown in the second photo. I give it a light coat of oil to help the bushing slide easily in place. I slide the dry gasket onto the engine, locating it onto the dowels; it will want to droop along the top so I add a few dabs of gasket cement along that area to hold it during assembly. Before I snug the bolts I visually verify that the gasket is in place around the entire circumference (third photo). Bottom all the bolts in a crosswise pattern and tighten incrementally. Finally, install the oil filler cap and dipstick, ensuring that their o-rings are in place. If needed, the o-rings are still available from Honda. Valve Covers: (Below) Pretty straightforward, but first I do a final check for debris using a bright light. I've been asked many times the secret to removal/installation of the rear cover on the Gen-2 — there doesn't seem to be enough side-to-side room between the subframe rails. There is not, so the trick is to fully raise the wire harness above the frame rail, then hold the left side higher as you remove or install the cover. Finally, visually check that the rubber gasket is correctly seated all the way round. (Below) The front cover sets in place easily from the front side (this is one reason I remove the radiator during valve service). The bolts are seated with their gaskets then torqued sequentially to about 9 Lb/Ft, or 108 inch-pounds. Ensure that those bolt gaskets are installed right-side up; Honda thoughtfully stamped "UP" on the upward-facing side.

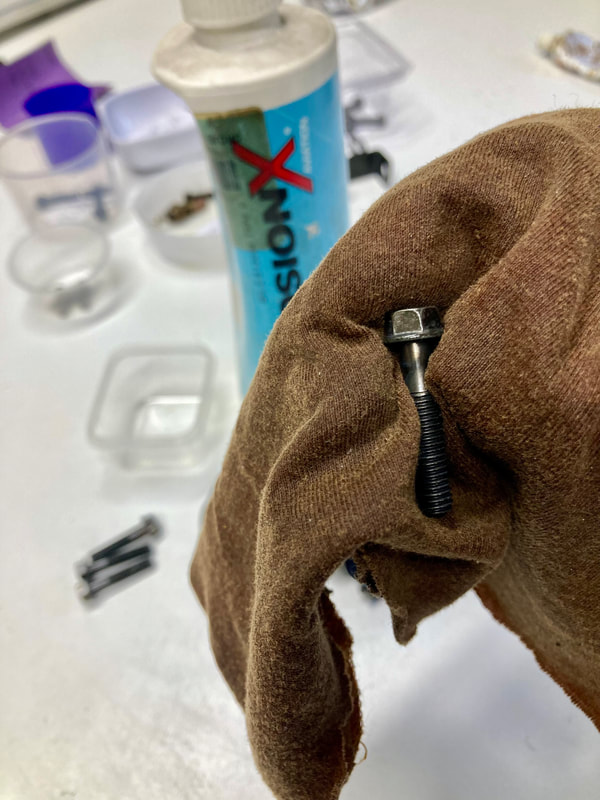

At this point I blow out the spark plug holes with compressed air (spark plugs in place). Note that there's water drain holes for these cavities 90° to the outside of the engine casting, which should also be cleared with compressed air or a long wire, if clogged. I do this along with swabbing the spark plug holes clean before valve cover removal. Finally, I refill the crankcase with oil, and with the engine buttoned up, I'll move on to the cooling system install. In an earlier post I detailed how I assembled some Gen-2 engine & valve covers in preparation for installation. With all that pretty powdercoating you'll want the various fasteners to look their best, and here's how I approach that detailing. I find fasteners and brackets in all manner of condition; most are salvageable and some are just too far gone, but many are specific, non-generic fasteners so you don't always have the luxury (or budget) to replace with new. The first photo shows how the 6mm clutch/alternator cover bolts looked — corroded, dirty with a generally "dry" metal appearance. After cleaning, I gently buff the fasteners with a soft rotary brass or steel brush on a medium speed and see how well that works. I also wire brush the threads. Resist the urge to use a bench grinder-style wire brush, you will remove any paint or plating and end up with rusted bolts. I then wipe them with a metal protectant, like Corrosion X or ACF-50 which will help bring back the dark color. There's about 25 of these bolts for just the engine and valve covers, so you'll need a bit of time. Alternatively, these bolts are still available from Honda; about $40 would cover all the clutch and alternator bolts. Small brackets also benefit from this effort — the fuel pump holder is pictured with some finished bolts. The chrome valve cover bolts are typically stained with dirt and surface rust. Using 0000 steel wool and chrome polish, the bolts came back to new.  The number of bits and bobs needing detailing seem endless on these projects. Here's a small selection showing how I keep them separated and labeled. Clear sandwich bags are a popular alternative, but I like to have the parts out where I can see them so I just use various size containers. This also makes it obvious which fasteners and brackets are in still in need of a cleanup. Yes, it a labor-intensive chore but, yes, it takes your project to the next level. NOTE: I have no affiliation with this sale  Click on image for the BaT link Click on image for the BaT link What: 1986 VFR700 F2 Why: A great rider Where: Naperville, Illinois Price: No reserve auction ends Nov 25 For a few more details, please refer to my earlier post (10/13) when this former project was offered on FB Marketplace. Project 27 is now live on Bring-a-Trailer with no reserve. The seller now notes an oil leak, which he reckons is from the rear cylinder valve cover which should be easily addressed. Good luck to seller & buyer. Earlier this month, at the EICMA trade show in Milan, Italy, Honda dropped this little bomb on the moto industry. In development is an all-new V3 engine featuring what would seem to be a stunningly good idea: an electrically-driven, computer-controlled mini-compressor — an electric turbocharger, if you will.  Not a lot of details were provided except to state that this engine would be a 75° V3 (two cylinders in front, one in back) "for larger displacement machines." Honda claims the electric turbo to be an industry first, its huge advantage being the ability "to control compression of the intake air irrespective of engine RPM, meaning that high-response torque can be delivered even from lower RPM." Honda has dabbled in the V3 layout in the past with the NS400R and exhaust-driven turbo-charging back in the '70/80s with the CX500/650 Turbo, but this independently-driven electric compressor has the potential of addressing the deficiencies of that traditional turbo design. No word on the first model planned for the new engine, but the photos suppled showed this very cool trellis-style, single-sided swingarm, sportbike-looking frame — the engine and drivetrain barely twice as wide as the rear tire. I'm thinking a 750cc new-age Interceptor with ~150 horsepower and gobs of mid-range torque. Sounds like fun!  Click on image for the eBay link Click on image for the eBay link What: 1984 VF700F Interceptor Why: Low-mileage, original Where: Bainbridge Island, WA Price: $4500 OBO By the time a classic vehicle reaches four decades of age, finding one with the magic combination of very low miles and unmolested condition is something of a holy grail. Here we have such a find. Showing only 5597 miles and represented as a 2d-owner bike and always garaged, this example appears to be complete with all its original bits and less than perfect finish commensurate with its age. There's road rash on the left muffler and general scuffs and light corrosion, but still a fine 10-foot example. The fuel tank was replaced with a NOS original, the front fairing repainted sometime in the past and some maintenance completed ten years ago. A week spent detailing and maybe refurbishing a handful of items would take this survivor to the next level. Our seller has put on only 200 miles in his decade of ownership. His description indicates that the carburetors are in need of attention, and I would attend to all the fluids, source a replacement muffler and ditch those old Shinko tires, but this would be a great example to take up a notch for the perfect classic, everyday rider. At closer to $4K this would be a great find on a first generation Interceptor. I've been busy for several weeks preparing all the large and small bits for final assembly on Project 41, a 1987 VFR700 F2. The goal is to have everything sitting ready on the shelf when its time comes. The bodywork is finished, tires mounted, small bits gathered and refurbished and the machining required for the fork emulator install has been completed. I'm currently awaiting delivery of the new shock which will allow the rear of the bike to be assembled, the build proceeding quickly from there.

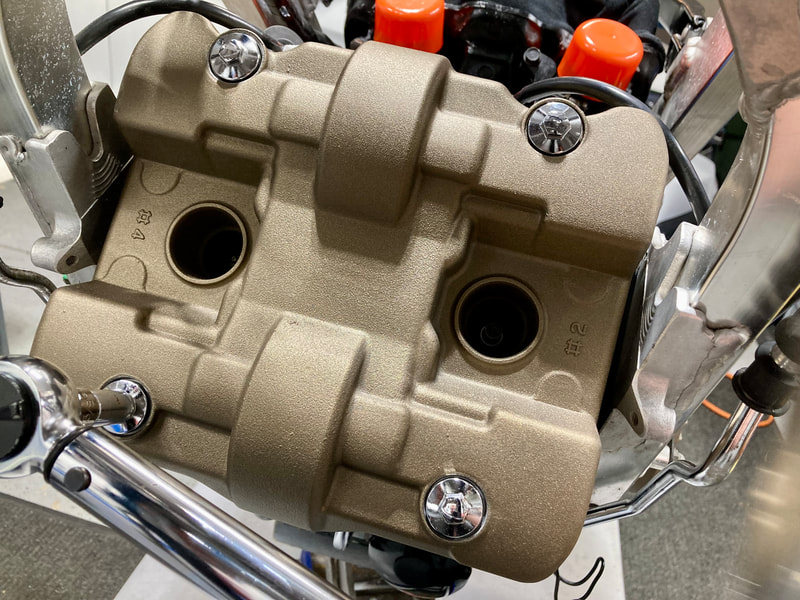

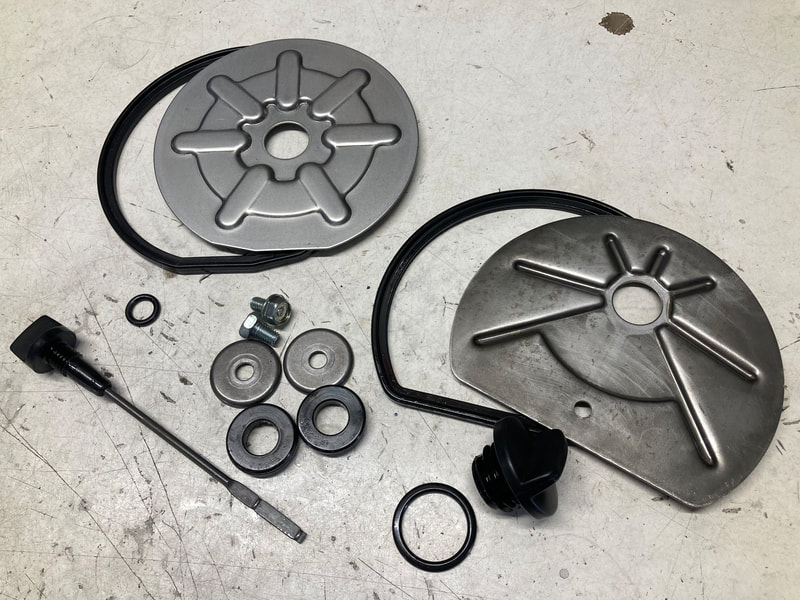

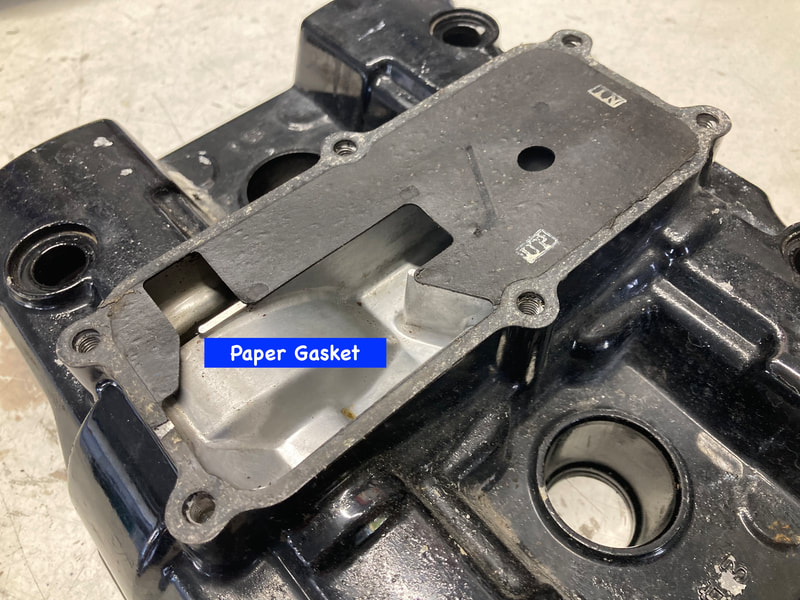

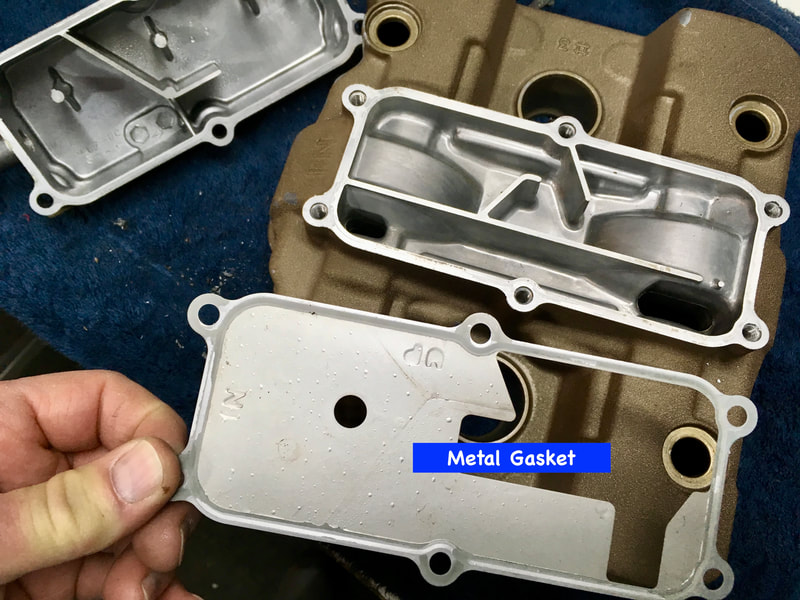

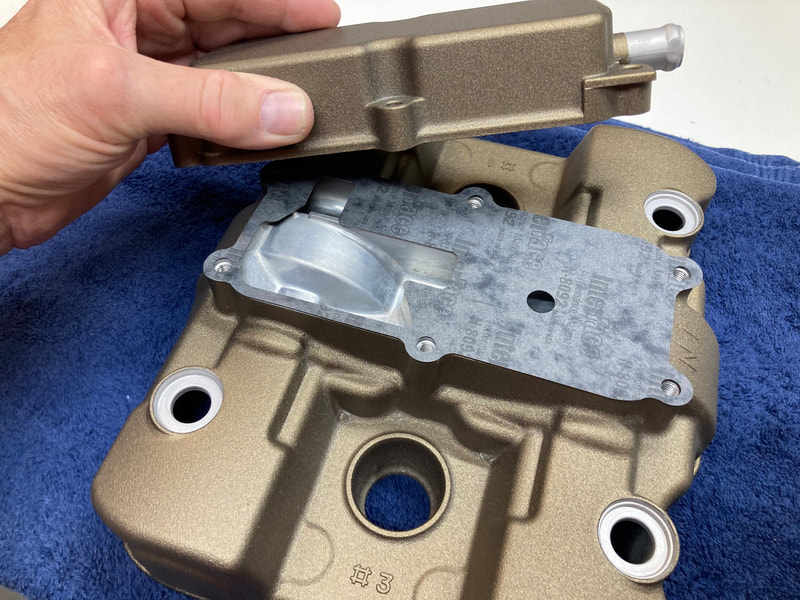

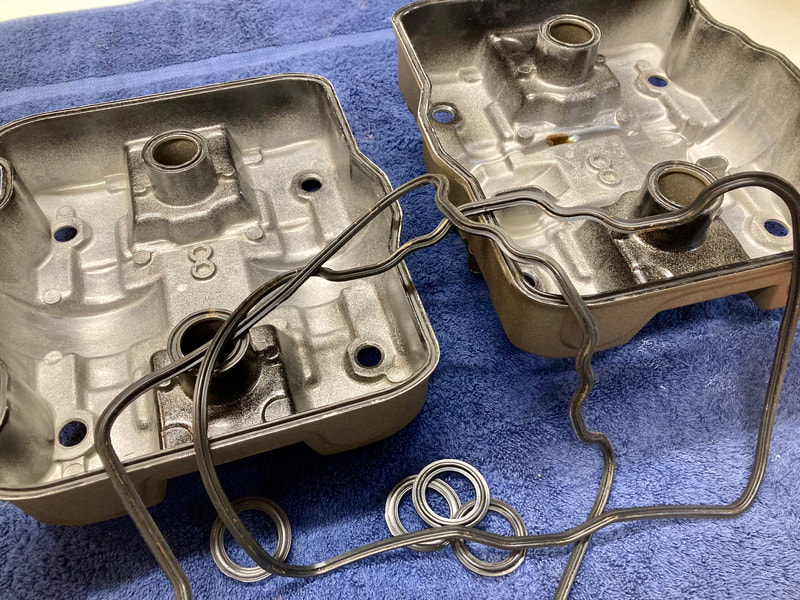

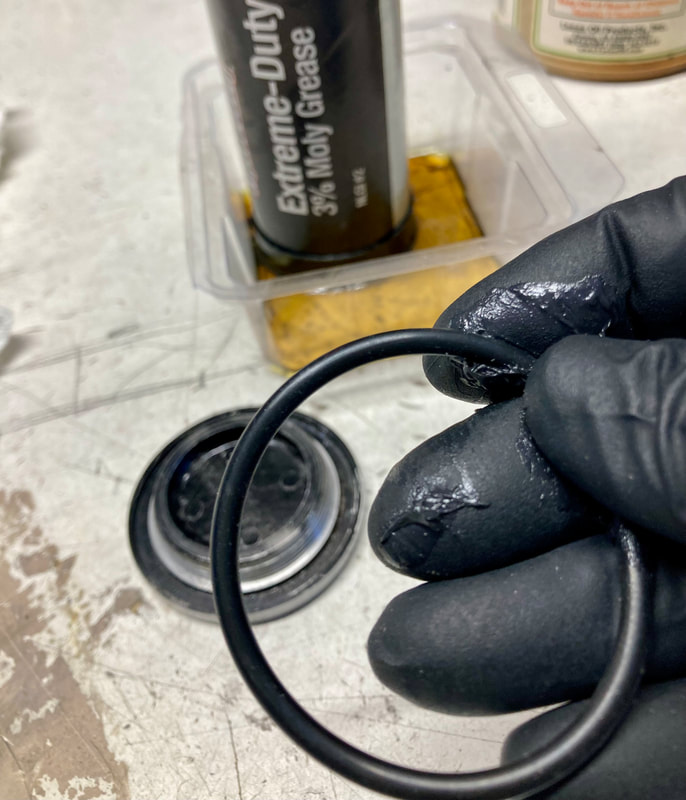

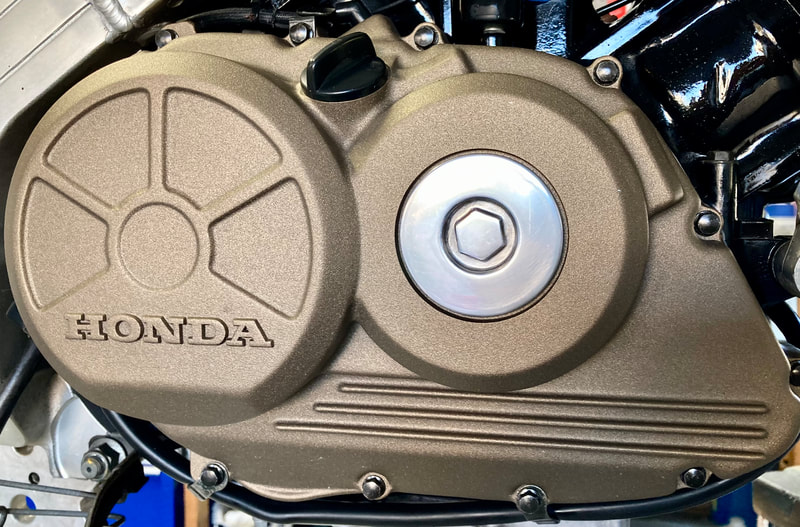

I recently received Project 41's engine covers back from Tom at Tom's Cycle Recycling (https://www.facebook.com/Tomk1960/) showcasing his usual powdercoat perfection. Finished in Textured Gold Dust, the idea is to mimic the unique-colored covers from the 1986 VFR, while providing a deeper, richer color. These covers are special — they're made of magnesium, shared with more exotic factory-prepared machines like the RC30 and RC45, IRRC. To my knowledge, Gen-2 VFRs are the only generation of standard production models to sport magnesium covers. Let's go through my part of the process to get to the finished product, beginning with disassembly. Powdercoating requires media blasting and baking in high heat, so everything must be stripped from the assemblies. For the clutch/alternator covers, this begins with removal of the (sound?) baffles on the backside of the covers. A single bolt holds each plate and its rubber gasket, which are lock-tighted in place, requiring an impact tool for removal. (click on images to enlarge) For the valve covers, I'll need to remove the rubber gaskets and the rear cover's oil baffle assembly, where I discover a paper gasket (a first for me) in place of the typical stamped metal (below). The metal is reusable, but the paper version shreds upon removal. Neither is available from Honda but, fortunately, a paper replacement is available from the aftermarket, about $13 on eBay. Once stripped down to the bare covers, I address any cosmetic damage. In this case only the lower portion of the alternator cover had some road rash. I smooth out the metal with a combination of light sanding discs on a die grinder followed by hand sanding till smooth. After Tom works his magic, I give all the parts a soapy bath and hot rinse to ensure nothing harmful is left behind, then assembly begins with remounting the oil baffle (below). Next, I'll assemble the side covers (below). I lay the sound baffle's rubber gasket in place, set the baffle in the gasket's groove and lay the rubber washer and its metal cap in place. After degreasing the bolt, I'll coat with red threadlock and tighten the bolt very securely. Note which side of the baffle plates face upward. Next, I install the rubber valve cover gaskets (below). The Honda manual states to "apply sealant between the gaskets and cylinder head covers." I've never found this to be necessary, except to add six or eight dabs of gasket cement or similar (center photo) in order to hold the gasket in place when it's tipped upside down during installation onto the engine. I let the cement set up for a few minutes and then test that the gasket stays in place long enough to allow installation. The manual also states, "apply sealant around the projections of the gasket." I have no idea what they're referring to, but I've never had a reused valve cover gasket leak when installed dry. YMMV. Finally, I spend some time with the timing hole cover. The cover can be powdercoated, of course, but I like the contrasting polished aluminum look. After chemically stripping the original black paint (in this case) I wet sand with three or four grits till I'm happy with the look, then coat with Sharkhide to protect the raw aluminum finish. The manual wants us to coat its threads with moly grease, and I also add some to the o-ring, which I always reuse. Snug in place with a 17mm socket, and these parts are ready to rejoin the engine…a future post.

Click on image for the eBay link Click on image for the eBay link What: "Norceptor" Why: I got nothin' Where: Dallas, Texas Price: $3600 opening bid With full appreciation that our Honda V4s are great engines and relatively unique in the classic moto world, this build is still a head-scratcher. The practice of swapping Triumph/Norton/Vincent engines and frames was popular back in the day for one good reason: the sum could be made better than its parts. The Norton "Featherbed" frame, for example, was considered the gold standard of the 60's era production bikes so it kind of made sense and was a fun (and relatively easy) exercise. But this collection of parts is none of that. Based upon what appears to be a '73 Norton frame, complete with a single Lockheed disc squeezer up front (barely better than the drum it replaced), ancient drum out back, along with spindly tires and suspension, this bike will transport the rider back to the bad old days of British "dominance." Lest one assume I know not from whence I speak, I should mention that my first crankshaft-up restoration was a '72 Norton Commando roadster. I loved much about that machine (on a good day) but its performance was greatly derived from its relatively light weight, giving a good power-to-weight ratio (for the time) and helping to mask the weak suspension, brakes, and flexible frame. Inserting a heavy 80 HP V4, plus its cooling system, into a 1950's-derived chassis is the definition of going backwards in moto evolution. I really do appreciate folks who think outside the box and have the determination, time and skills to make it a reality, but some ideas just make more sense than others. I can't even imagine this thing going down the road at any speed ("frame welds need attention for riding again") but with an opening bid of $3600 and no title provided, that likely won't happen in any case. |

THE SHOP BLOG

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed